NILOTIC WANDERINGS

(April 2024)

(All the photos can be enlarged. Simply click on a photo gallery to get a full-screen slideshow, and right-click -> Open image in a new tab for photos posted independently of galleries.)

Preliminary fun

Reading Death on the Nile on the Nile.

(Photos by Sylviane Camus)

Outside the Horus Temple in Edfu, dressed as a supporter of Horus for his victorious return match against Set.

(Photo by Mireille Legros)

In the Tahrir Square museum, reading The Romance of the Mummy, dressed with The Mummy, in the company of a mummy.

(Photo by Mireille Legros)

In the Tahrir Square museum, reading part of the Book of the Dead in front of part of the Book of the Dead.

(Photo by Mireille Legros)

Finally, one of my very rare selfies was taken in front of the Pyramid of Nicolas Cage at Saint-Louis Cemetery No. 1 in New Orleans, on 27th July, 2022:

For more on that trip, see of course my "musical stroll" entitled "Dix jours d'un concert à l'autre à la Nouvelle-Orléans", published in the journal Miranda.

...and I have tried to do some sort of a remake in front of the Pyramid of Menkaure in Giza:

10th April

The Ptolemaic Temple of Horus, in Edfu, near Aswan, Upper Egypt, was the first stop on this journey along the Nile, on a cruise ship called the Nile Capital. This visit, like all those we were going to make in Upper Egypt, took place under the direction of an affable, funny and captivating guide, mixed Arab and Nubian, former boxer and footballer, by the name of Amr (pronounced Amro).

Mythologically, this is where the falcon god crushes his uncle Set, to avenge Osiris, the deceased father of Horus and brother of Set, whom the latter cut into pieces.

The traditional design of the temple, with its courtyard open to all, followed by a columned hall called "hypostyle", reserved for high society, and a sanctuary where only the priests and the pharaoh could go, gives the guide the opportunity to introduce us to the religious architecture of ancient Egypt.

See page for author, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Here in particular is the sanctuary, occupied, in the case of Edfu, by a replica of the solar barque that was there initially (as was the case in all the temples (to allow the god(s) of the temple to sail on the celestial Nile) generally "parked" either in the sanctuary, or in the small rooms and chapels at the back of the temple, adjoining the sanctuary):

(Photo by Sylviane Camus)

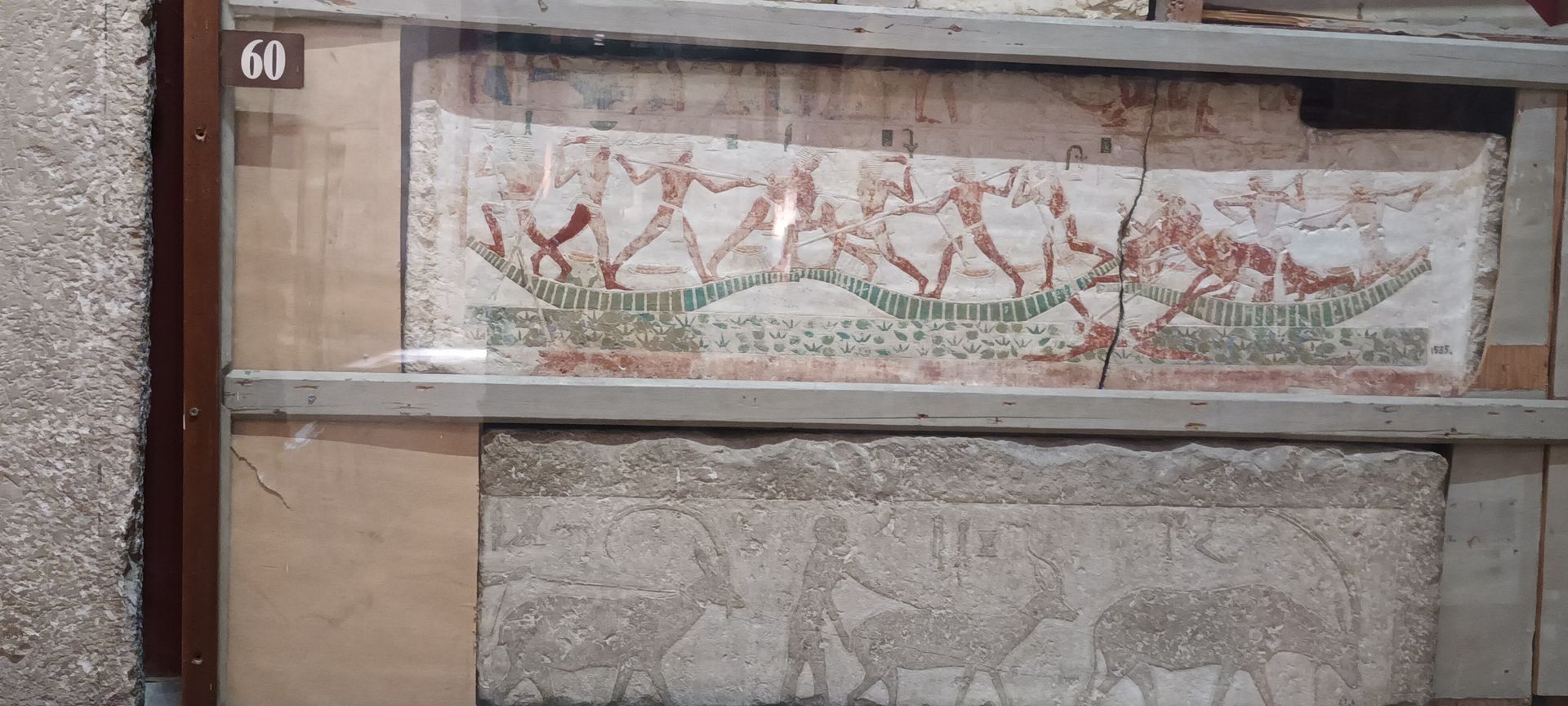

... and taking those barques out, and parading them (as shown on the bas-relief below), and symbolically parading the god with them, was part of the religious ceremonies that were held regularly during official celebrations:

We were also introduced to three of the main types of columns in ancient Egyptian buildings: columns with capitals scultped in the shape of a (closed) lotus (called lotiform columns), in the shape of palm leaves, called palmiform columns, or in the shape of papyrus leaves, called papyriform columns:

This is lotiform.

(Photo by Mireille Legros)

The left-hand one is palmiform. The right-hand one is papyriform.

So, are you able to recognize them, on the photos above and below?

(We'll talk about Hathoric columns later. That's a whole other story.)

To conclude about Edfu, here is a little family/group pic:

(Photo by a helpful passer-by)

After the lunch break, the boat took us outside the temple of Kom Ombo, a construction from the same period as Edfu's, which is very similar in its structure, except that it is a double temple , dedicated to both the crocodile god Sobek and Haroëris (an avatar of Horus whose name means "Horus the Elder").

(The last photo in the gallery above was shot by Sylviane Camus)

We also had the opportunity to admire the "nilometer" of the Kom Ombo Temple, which was used to measure and predict the flooding and receding of the Nile:

Finally, because the temple is dedicated to Sobek, there is an odd little “crocodile museum” where you can observe numerous mummified Nile crocodiles:

11th April

On the next day, we visited Philae and passed by Elephantine. That schedule was all the more delightful as an amusing coincidence occurred: the day before, in my post-Kom Ombo reading, Linnet and Simon Doyle were pretending to go visit Philae to try to lose Jacqueline de Bellefort, while Hercule Poirot was really visiting Éléphantine. Besides, in this part of the book, all those characters have set their base camp at the Old Cataract Hotel, which we also passed by during the comings and goings of the day.

Today, "Visiting Philae" means visiting a magnificent temple from the Greco-Roman era, dedicated to Isis, and located on the island of Agilkia. It was originally on the island of Philae (and that's where Linnet and Simon Doyle claim to go in the book), but it was swallowed up by the reservoir of the Aswan High Dam in the 1970s. In the meantime, the temple was saved by being completely dismantled and reassembled identically on Agilkia.

The very good conservation condition of the temple, the island context, surrounded by the clear sky and the peaceful waters of the lake, as well as the awe at the idea of the incredible logistics of saving the structure, all contribute to giving the visit a magical atmosphere.

That was the morning visit. A motorboat (like the one below) had taken us to Philae and then took us back to the bus, which drove us back to the Nile Capital for lunch...

(Photo by Cecilia Camus)

... but not without a stop first at two Aswan stores, where the shopkeepers talked up and basically marketed their products to us (one sold essential oils, the other spices), and that gives me the opportunity to show some glimpses of the streets of Aswan, seen from the bus (including the facade of the spice store, and the wharf teeming with street sellers from which we had sailed in the morning):

(Photos by Cecilia Camus)

... and, besides the facade, here's a glimpse of the inside of the spice shop:

(Photos by Sylviane Camus)

In the afternoon, we took a felucca for a quick and picturesque tour of the island and coastal sites around Aswan.

Feluccas seen from a felucca.

Felucca a bit like ours, seen from ours. (Photo by Cecilia Camus)

Camus family sailing on the waves.

(Photos by Mireille Legros)

The Old Cataract Hotel (named after the first cataract (The Cataracts of the Nile are four rapids, and the first one, near Aswan, is the only one in Egypt. The other three are in Sudan.)) Besides Christie who started writing Death on the Nile there (and, as aforementioned, her characters at the beginning of the book, Amr insisted on reminding us time and again that François Mitterrand also stayed there.

(1st photo by Cecilia Camus, 2nd one by Mireille Legros)

Elephantine, whose name inspired several theories as to its origin (its ancient name evokes elephants and ivory, its overall shape on the map looks like an elephant's tusk)...

(Photo by Cecilia Camus)

... but according to our guide the reason for it is this rock, which is, in his mind, reminiscent of the shape of an elephant... Who knows?

(Photo by Cecilia Camus)

We also saw, from afar, the Mausoleum of Aga Khan III (1877-1957), the imam of the Nizari Ism'aili, a Shia community (which is rare in Egypt, the overwhelming majority of the country being Sunni):

(Photo by Cecilia Camus)

(Photo by Sylviane Camus)

And there was a musical soundtrack to all that, since the area is teeming with singers, whether young people floating up to the tourists' feluccas on surfboards, then clinging to them to serenade the passengers (thus giving a new meaning to the expression "surf music"), or a member of the crew who also sung to us while beating a frame drum with his hand. More or less the same playlist from one performer to another: "Alouette", "Il était un petit navire, "La Macarena" and "Waka Waka (This Time for Africa)", even if the crew member also added a local song in Arabic (before closing his own concert with a resounding: “Ça roule, ma bloule?!”)

(Screenshots made from videos filmed by Mireille Legros)

... then on another island, Sehel or Elephantine (Amr didn't specify) for a little tour of a traditional Nubian village:

(Photos by Cecilia Camus; the last four are pics of the school)

(Photos de Mireille Legros)

A beautiful view overlooking Aswan from a high hill next to the village.

In one of the village houses, a view of my mother as if I were Google Maps

On the hill, a family portrait on an auto-rickshaw (my facial expression conveys very well what I think of this mode of transportation).

(Photo by Mireille Legros)

12th April

ABU SIMBEL !!

In this case too, it was the previous evening, therefore the day before our visit to the temple that Ramesses II dedicated to himself, that Hercule Poirot and his cruise companions from the ship Karnak visited the same temple, leading up to a first mysterious attempted murder.

We left at four in the morning (as the temple was a three hours' bus journey away), had a break halfway for breakfast in the desert:

(Photos by Cecilia Camus)

...then the bus went on, bringing us ever closer to the Sudanese border, before turning towards Lake Nasser about seventy kilometers before changing countries (yet

staying in Nubia!), and that's how we ended up at the foot of the four famous giant Ramesseses who watch over the entrance to the temple of Abu Simbel — a colossal building dug out of the rock of Meha hill, which was (like the temple of Philae) completely dismantled and rebuilt, in the 1960s, to protect it from the rising waters of Lake Nasser following the construction of the Aswan High Dam.

I was even able to sit and lounge with them for a while, but they're not very talkative:

(Photo by Mireille Legros)

The interior of the temple also has its share of statues of Ramesses II, this time standing in the so-called "Osiriac" position, with his two scepters, nekhekh (or "whip" — interpreted as a fly chaser by some Egyptologists) and heka (meant to evoke a shepherd's staff), crossed in front of his chest:

There are also bas-reliefs which also glorify Ramesses II (obviously: it is his temple, made by him, for him, and even with him). For instance, the battle of Kadesh (Syria, 1274 BCE), which the English host Greg Jenner described,

in the historical BBC podcast

You're Dead to Me, as the first piece of "fake news" in history (inasmuch as Ramesses lost this battle against the Hittites, but convinced the Egyptian people that he had won it triumphantly) (in the words of our guide, this becomes: he won it triumphantly, but the Syrians claim he lost it):

(Photo by Mireille Legros)

Another "event" highlighted on a wall of the temple is the coronation of Ramesses, which is strongly mythologized since it is the gods Horus and Set who carry out the ceremony (Why the evil uncle Set, assassin of Osiris, god of the desert and of chaos? According to Amr, it was a way of cleaning up the symbolism around a god to whom the father of Ramesses II, Seti I, had been dedicated through his name (Seti, which means " faithful to Set")):

(Photo by Cecilia Camus)

As a result, since the prestigious pharaoh god Horus takes part in the coronation, we can imagine that a number of columns in the hypostyle hall are dedicated to him, but there are also some that represent the wife of Horus, the goddess Hathor — thus, as the temple's symbolic system suggests that Horus directly sponsors Ramesses, the same is suggested regarding Hathor and Ramesses's wife Nefertari:

(Photos by Cecilia Camus) (except the last one, the wide shot: photo by Mireille Legros )

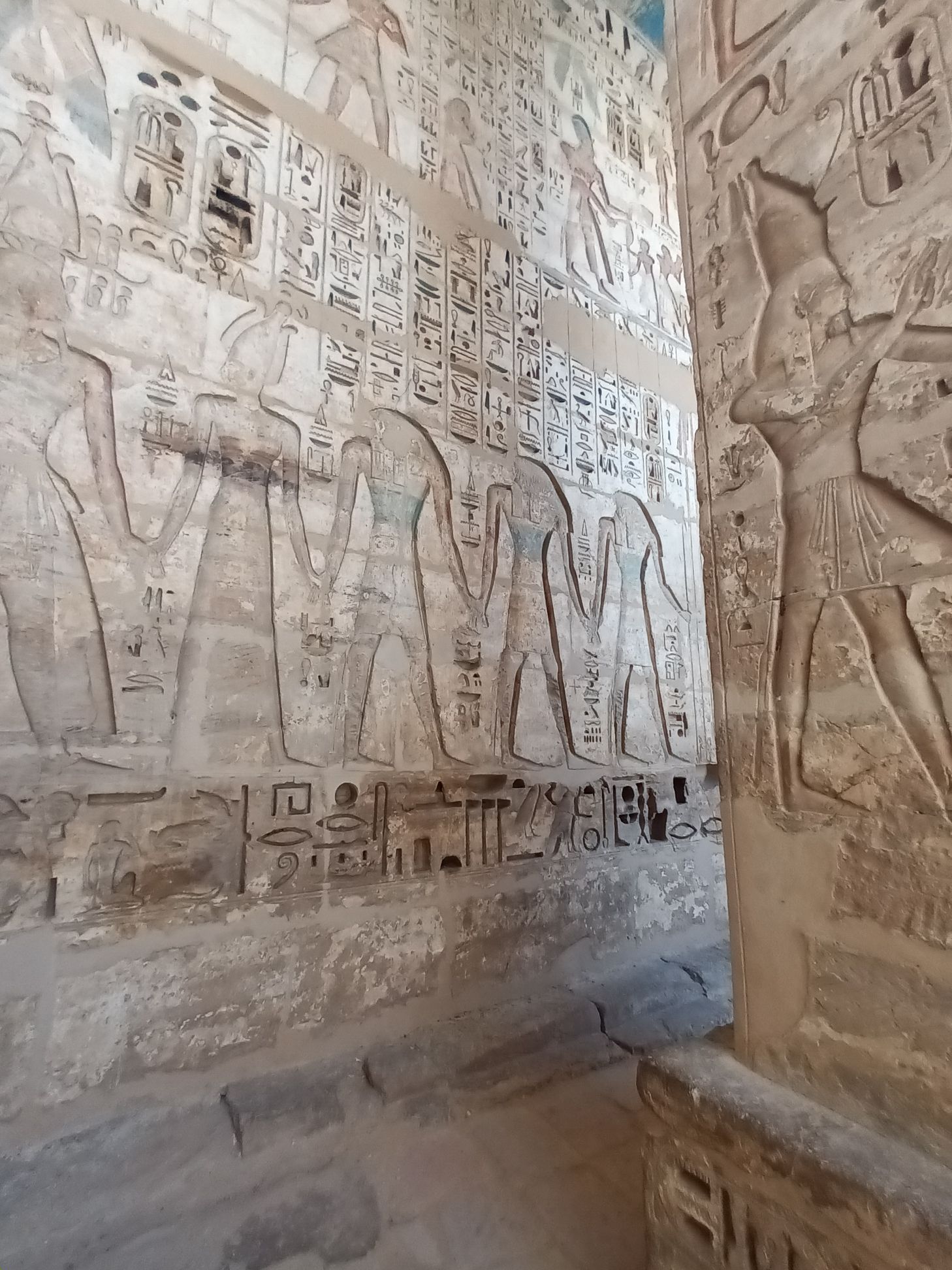

The many small rooms adjoining the hypostyle hall abound with repetitive bas-reliefs depicting Ramesses II presenting offerings to the god Horus (since the idea of this temple, in addition to the celebration of Ramesses as a military leader and his own elevation to the status of god, was also for him to take on the function of priest):

(That photo was shot by Cecilia Camus)

As for the sanctuary, it contains, again, four statues of Ramesses II, sitting (as he is on the monumental facade, but in a less epic, more meditative atmosphere):

(Photo by Cecilia Camus)

View of the entrance to the sanctuary (Photo by Mireille Legros)

Next to his temple, Ramesses II also had one erected to Nefertari, proclaiming her a goddess as he proclaimed himself a god. (That one too was carved into the rock, originally in Ibshek Hill, but it was also moved to avoid being submerged by Lake Nasser). It is notable, however, that this temple is significantly smaller, and that even the entrance is only decorated with two statues of Nefertari, and four of Ramesses! 🙄

So I had a small conversation with Ramesses, told him how much of a douchebag he's being.

(Photo by Mireille Legros)

I managed to make him see reason (a little), and the small hypostyle hall thus turned out to really revolve much more around Nefertari, who is likened to Hathor by numerous representations of the goddess, and in particular by the fact that the columns are systematically "Hathoric columns", whose capital is decorated with the face of Hathor, recognizable by her cow ears.

We don't seem to have any photos of the Sanctuary of Nefertari. Mine are blurrier than if my camera had gotten drunk with Ramesses, and my traveling companions don't seem to have taken any. On the other hand, here are some pretty photos of Lake Nasser and its surroundings (since we were, precisely, on its surroundings):

Nautical interlude

Since the afternoon of April 12th and the entirety of the April 13th were spent exclusively sailing from Aswan to Luxor, it is a good time to place some glimpses of the Nile Capital, the ship that was our floating home for seven days (April 9th to 15th) — even though those photos were taken on other days than the 12th and the 13th.

First, what does it look like from the outside? Well, first of all, it's not easy to take a picture of it, because the Nile cruise boats always dock in a row, so that, to get on yours, you generally have to go through the others. For example, on the photo below, the Nile Capital is the last boat on the row, so you can't really see it:

(Photo de Mireille Legros)

Here's another example, in action, of a boat akin to ours, seen from ours:

(Photo by Cecilia Camus)

Does it mean that we really have no pic of the Nile Capital? Actually we do, though you can only see part of it on the picture, but here it is:

(Photo by Mireille Legros)

Now, this is what the

sundeck looks like:

Cecilia Camus's version:

Mireille Legros's version:

Here are some views of the Nile shores, taken from the comfortable armchairs of the inside decks:

+ a few pics of the comfortable armchairs of the inside decks:

(Photos by Sylviane Camus)

And now here's the bar (with a glimpse of the stairs in the lobby):

(Photos by Mireille Legros)

... and the "'Nubian dances and songs' special night" version (Photo by Cecilia Camus)

The entrance to the restaurant (during "the special 'Oriental' night" — on other days, the waiters pictured there wore suits):

(... or cooks' uniforms...)

(Photos by Cecilia Camus)

Finally, the

rooms (four photos by me, then three by Cecilia Camus, then one by Mireille Legros):

... including a glaring example of the creativity of the room cleaning staff (first and last photos by Cecilia Camus; the others are Mireille Legros's):

Oh, actually we do have some photos taken on April 13 (photos of the Esna lock, and especially of the merchants who approach the cruise ships in small boats to try to sell clothes and souvenirs to the passengers:

(Photos by Cecilia Camus)

... and since we're on the topic of the Nile's "hawkers", let's look a bit at the Nile's garbage collectors too:

(Photo by Sylviane Camus)

So now, to summarize those first few days:

14th April

An extreeeeeemely rich day in Luxor (built where the ancient pharaonic capital of Thebes was).

We began with a visit of three tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

Before that, were treated to a short general introduction by Amr in front of the entrance to the tomb of Ramesses VII (the first tomb discovered in the Valley), even though we did not enter that specific tomb (and the guide would not accompany us into any of the tombs — apparently, they don't have the right to do so (he claims it's because dead pharaohs and their friends the gods don't really like guides; maybe it's rather because there is a singular lack of room in the tombs, and there are a lot of people, and gathering around guides the way it's easily done in temples would be a little trickier in that case)).

(Photo by Cecilia Camus)

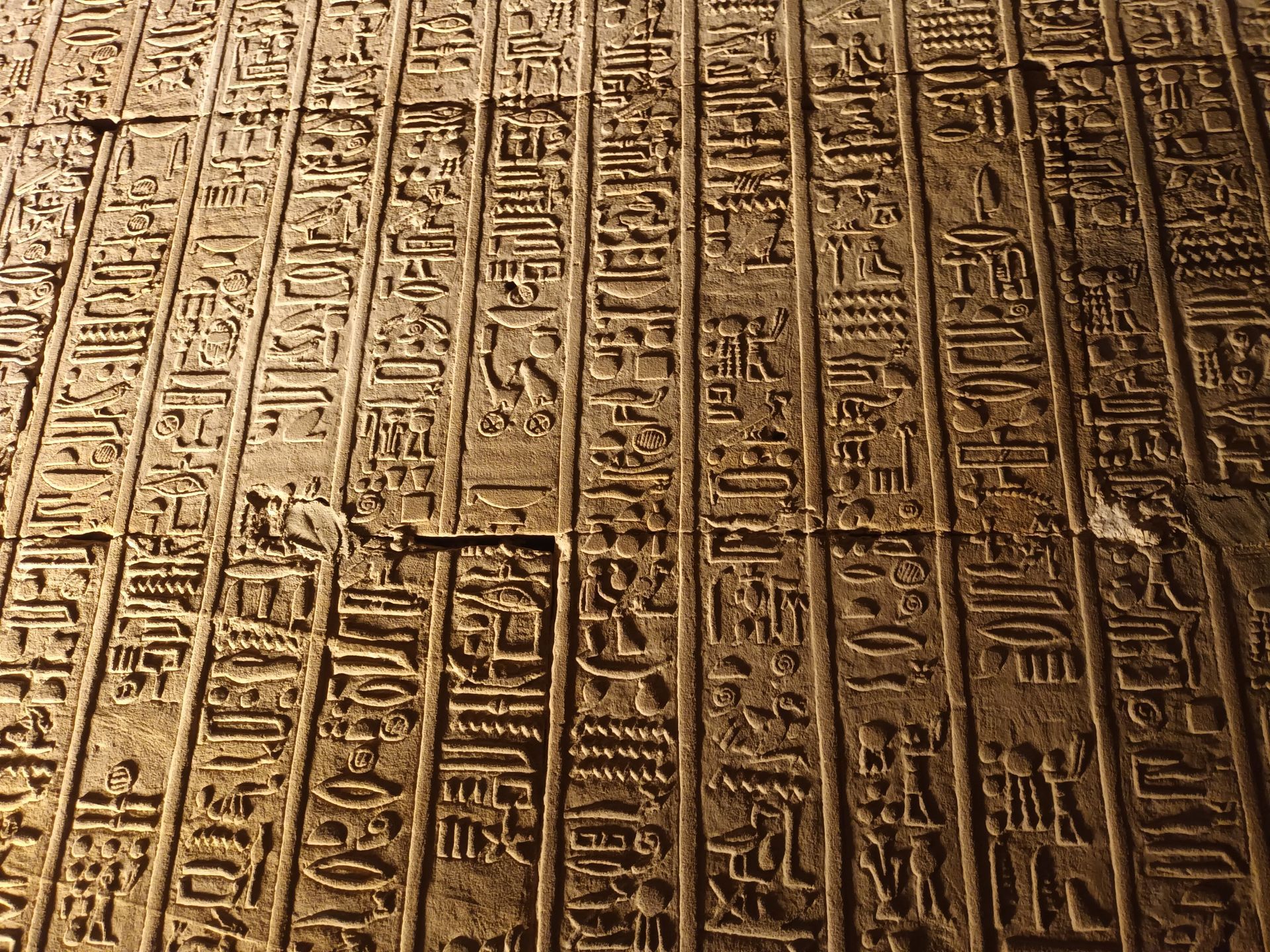

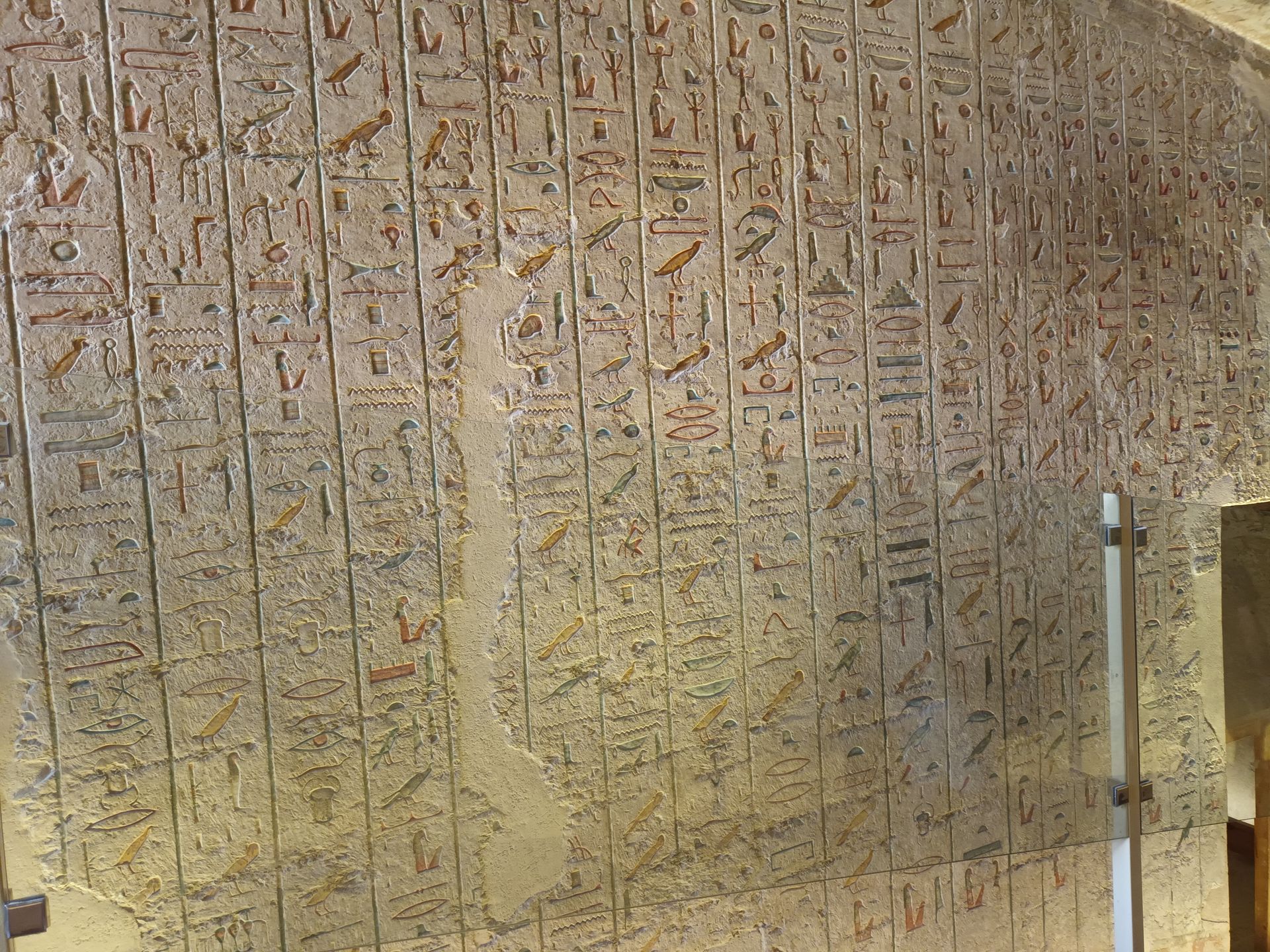

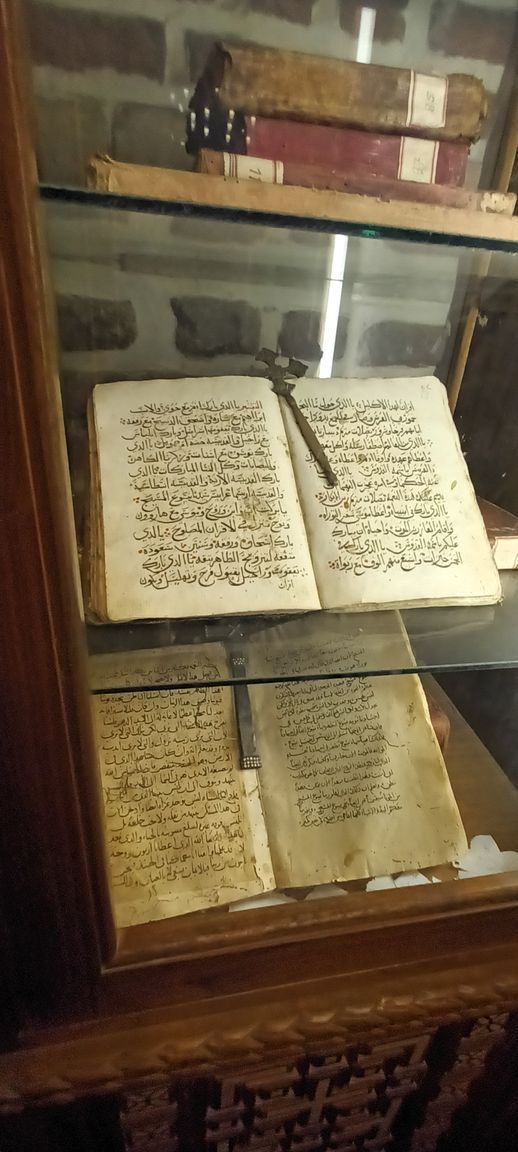

When we then entered the tombs of Ramesses IX and Ramesses III, we were amazed. The evocative graphic universe that we had already been able to contemplate on the walls of temples, based on scenes engraved in stone, in which iconic figures stand on decors covered with hieroglyphs, two kinds of images that complement each other to tell stories in two different visual modes (that of representation for the scenes themselves, that of an astonishing mixture of verbal storytelling and graphic symbolism for the hieroglyphs), all of this comes to life (paradoxically) on the walls of the tombs, because in this underground and confined space, the dazzling colors with which these sacred decorations were adorned at their birth are much better preserved. And so this universe (here completely eschatological, with hieroglyphic sequences made of excerpts from the

Book of the Dead or the

Book of Caves, recounting the journey of the deceased in the afterlife, and scenes that represent the same journey) shift from the grey of stones two sublime four-color graphics, like an immense mystical comic strip that covers every corner of the walls (and, as a result, surrounds and envelops us in a dizzying fashion).

(Photo by Mireille Legros)

(Photos by Mireille Legros)

Some watch the trains go by. Here I am looking at the solar barques transporting the etheric doubles (or "ka") of the dead across the Duat, to meet the psychopomps (Thoth, Anubis, Osiris, etc.) who will carry out - and the 42 judges who will witness — the weighing of souls (materialized by the actual weighing of the heart of the deceased).

(Photos by Mireille Legros)

(Photos by Mireille Legros)

The rest of the Valley of the Kings we saw mainly from the bus, even though we were going to stay a little longer that morning in the Theban necropolis (which extends over the west bank of the Nile opposite Luxor and includes the valleys dug with tombs (Valleys of the Kings, Queens, Nobles and Artisans) and a number of mortuary temples) and return there the next day to visit other parts of it.

(The second set of photos was shot by Mireille Legros, and the last photo shows old abandoned houses built in a time when the inhabitants of the region had a house on the banks of the Nile, and a house in the mountain where they migrated during the flood of the river, a practice that became less necessary with the construction of dikes to regulate floods, and useless after the construction of the first Aswan dam at the turn of the 20th century.)

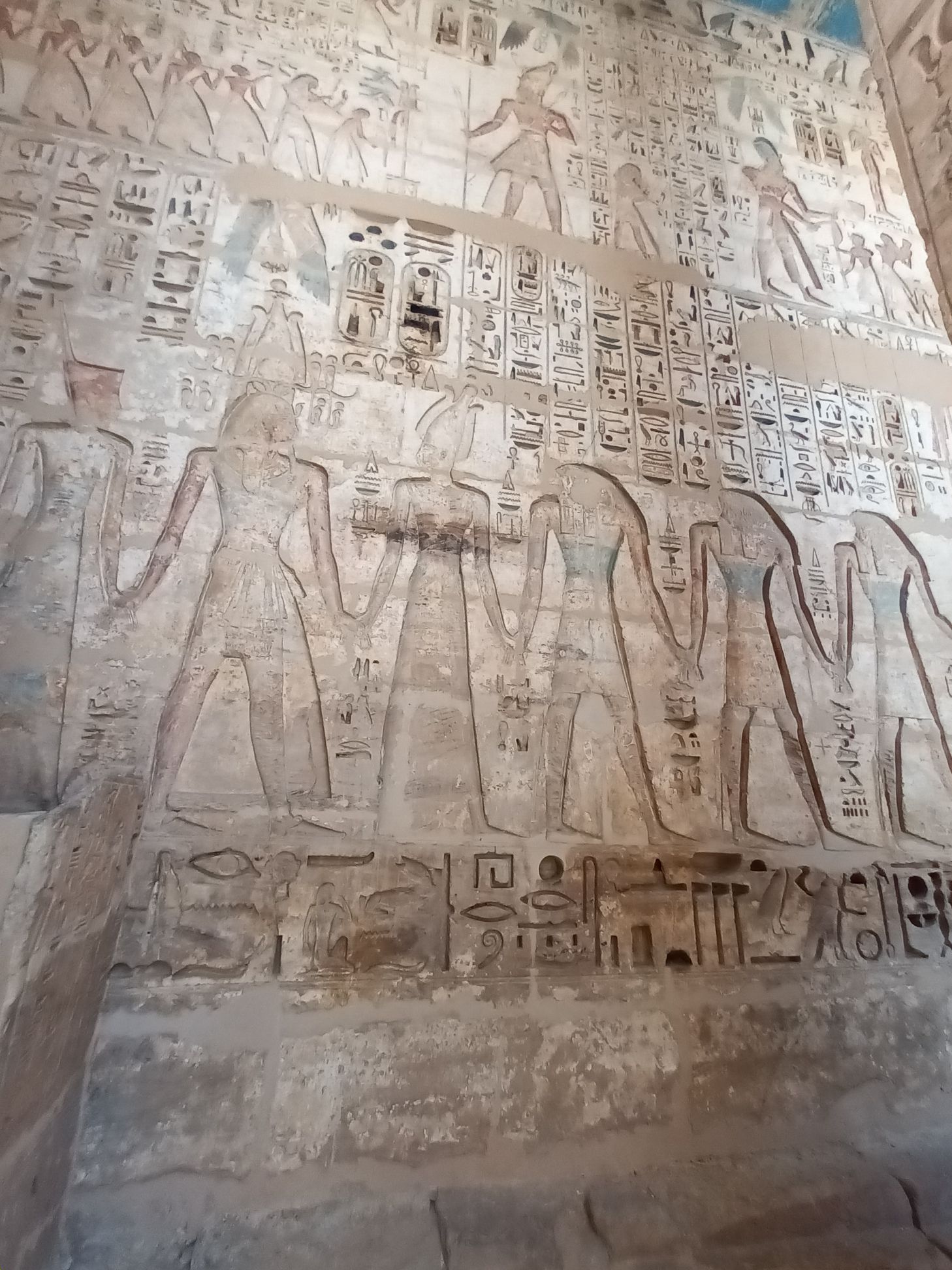

We moved on to the "mansion of millions of years" of Ramesses III, at Medinet Habu (still in the Theban necropolis). This type of temples dedicated to the deified pharaohs who had them built are considered as a type of mortuary temple even though they were not intended to serve as burial places. So the temple of Medinet Habu is often called "mortuary temple of Ramesses III".

What is striking in the aesthetics of this temple is the sunken-reliefs (or intaglio) which adorn its walls: the scenes represented, the hieroglyphs that surround them, are all dug very deeply into the stone, so that we see them very clearly and from a distance — and so that today's tourists can stick their hand into them, which they often photograph themselves doing (and so did we). According to the guide, the famous strike of the workers of Deir el-Medina, the village of the artisans who built the tombs and mortuary temples of the necropolis (the strike famous because it was the first strike in history) occurred because of the sunken-reliefs of this temple, which required more work than usual from the workers, so they were unhappy that Ramesses III did not increase the food rations they received as wages in kind (according to the Great Sage Wikipedia, the cause of the strike was rather delays in food ration distribution, not particularly related to the temple — but indeed during the reign of Ramesses III; is there a kind Egyptologist in the room to tell us whether Amr or Wiki is right?)

The two courtyards that follow the entrance to the temple are extremely well preserved, with even paintings intact in several places. On the other hand, the two hypostyle halls and the sanctuary were almost entirely destroyed (probably by the great earthquake of 27 BCE), leaving only the feet of columns between the surrounding walls.

(Photos by Mireille Legros)

(Photo by Cecilia Camus)

Then we were taken to one of the stonemason workshops found on the west bank of the Nile. The guide suggested that we were at the "Valley of the Artisans", but we would not see the tombs and the village of the artisans of the Theban necropolis until the next day, so I don't know if we were very close to this site or not.

(Photos by Mireille Legros)

We got a demonstration of how they make their alabaster crafts...

(Photo by Mireille Legros)

... then one seller at the adjoining shop was inspired by my T-shirt to insist on selling me this basalt statuette of Thoth:

Returning by bus to the east bank to join the boat and have lunch, we stopped briefly to photograph the two colossi that stand near the exit from the necropolis into Luxor — one of which has been called the “Colossus of Memnon” since the authors of ancient Greece dubbed it this way, in tribute to the eponymous mythological Trojan warrior - but in reality, the two colossi represent pharaoh Amenhotep III, and stood outside the entrance to his "mansion of millions of years", of which little remains. The colossus that is partly destroyed was made so by the earthquake of 27 BCE.

Some glimpses of Luxor, including the colossi:

(Photos by Mireille Legros)

(Photos by Cecilia Camus)

The first visit of the afternoon is to the gigantic temple of Amun-Ra, in the heart of the immense religious complex of Karnak, on the east bank of the Nile (the bank where the city lies, as opposed to the west bank which is that of the necropolis).

The building of the temple was started under Amenhotep I, then extended and enriched by all the following pharaohs over successive reigns. to become the wild, crazy edifice that it is today (thanks to Ramesses II among others) with more than 1 km² of surface area, and a large hypostyle hall built under Seti I, which no longer has a roof but contains 134 columns (usually, there are more like 12, in the hypostyle halls of "normal" temples).

To begin with, here is the entrance, which is accessed through a dromos (an avenue lined with sphinxes (in this case, criosphinxes, with the body of a lion and the head of a ram) which connects this temple to the Luxor Temple, which we would visit in the evening (the dromos dates back 3400 years, and was completely restored more recently (end of work in 2021)). In addition to the criosphinxes, there are, as usual, the vast pylons, as well as, in this case, colossi representing Ramesses II (surprise!) when we pass the pylons, and, before the pylons, on the side, a small Muslim monument (I think it is a mausoleum, I did not hear well when the guide spoke about it, and the Internet has decided to be of no help with this information, so if you know, please tell me).

The temple also contains obelisks with an interesting historical background. Of the two seen below, one is the only one remaining from a pair of obelisks erected during the reign of Thutmose I, and the other (the one half-surrounded by a wall) is the sole remnant of another pair, created during the reign of his daughter Hatshepsut (who after the death of her husband and half-brother, Thutmose II, became regent of her stepson Thutmose III, then was crowned and proclaimed pharaoh, thus imposing a joint reign on Thutmose III when he reached his majority). After the death of Hatshepsut, Thutmose III carried out several campaigns of mutilation of monuments built by her order, a way of trying to erase her then unprecedented and daring status as "female pharaoh" (rather than simple regent), and the wall built around her obelisk in Karnak, to hide it, is one of those attempts at relegation undertaken by this jealous male chauvinist against his stepmother's heritage.

The two obelisks seen from the hypostyle "hall":

The obelisk of Thutmose I:

The obelisk of Hatshepsut and its surrounding wall:

... and sitting near the wall and the obelisk, here is the perpetrator of the architectural assault against Hatshepsut, her stepson Thutmose III:

However, Hatshepsut had her little revenge, not only because the long-fallen wall does not hide her obelisk at all, but also because her other collapsed obelisk was put back into service in 2023. All that remained was the upper part of the obelisk, so it is smaller than the other two, but it stands now next to the sacred lake of the temple (and the granite monolith topped by the giant scarab Khepri, an artifact rescued from the mansion of millions of years of Amenhotep III (the temple that should be all around the colossi of Memnon) and transferred to Karnak for... basically superstitious tourists to walk in circles around it, hoping that it will make some of their wishes come true (the number of spins depends on the type of wish: seven to find love, five or six to protect your lloved ones, things like that)).

Then, after the columns and the obelisks, as the temple is gigantic and seems to be without end when you walk through it, there are many other ruins of courtyards, chapels and antechambers to explore:

Behind the first pylon, there is a vast courtyard lined all around, like the road that leads to the temple, with rows de criosphinxes (favoured here over androsphinxes with human heads because the ram is an animal symbolically tied to Amun-Ra, to whom the temple is dedicated).

Finally, the climax of the show as far as I'm concerned: in Karnak I found the oldest smiley emoticon in the world:

After Karnak, the guide took us for another consumer break, this time in a store where papyrus is made and sold. We were treated to a brief but interesting demonstration of the manufacture of this material, then the harassment Egyptian shopkeepers always engage in allowed them to sell me a papyrus on which Horus and Hathor contemplate my first name in hieroglyphs, inscribed inside a cartouche (like the names of pharaohs on the walls of temples).

(Photos by Cecilia Camus, except for the third one: photo by Mireille Legros)

We also went to a jewelry store, where the sellers, very unusually, left the tourists alone, even more so in my case as I was clearly not the target anyway. They had a corner that displayed cheap and kitschy bits and pieces for sale too, so I bought a magnet for my fridge, depicting a scene that's absurd (Tutankhamun, strangely wearing his famous funerary mask, looks at his stepmother, Nefertiti, and between them are the pyramids of Giza even though Tutankhamun was buried in the Valley of the Kings, and Nefertiti was queen when the capital was Thebes then when it was Amarna, not when it was Memphis) but, for that very reason, all the funnier.

Finally, the day concluded with a visit to the Luxor Temple at sunset. Like Karnak (even if it is much smaller), this temple is dedicated to Amun (in his dual aspect of Amun-Ra the solar god and Amun-Min the ithyphallic god), and is the work of several pharaohs (the oldest parts dating from Amenhotep III and Ramesses II). There are giant statues of these pharaohs, including, of course, Ramesses II. There are impressive peristyle courtyards.

There is an obelisk in front of the entrance (originally there were two, but the other one is at La Concorde, in Paris, having been given to King Charles X by the Muslim king of Egypt Muhammad Ali. In reality, both obelisks were offered to Charles, but only one was actually brought to France. It was difficult and tiring enough. No need for a second one.

There is also a mosque inside the temple: the Abu Haggag mosque, named after the eponymous local saint, mystic Sufi Sheikh Yusuf Abu al-Haggag. The mosque was built in 1244, and contains Abu al-Haggag's tomb.

The temple is located at the other end of the dromos that starts at Karnak, and the pharaohs celebrated the cult of Amun (and of the "Theban triad", composed of Amun, his wife Mut, and their son Khonshu (yes, the god from the Marvel series Moon Knight 😛)) by transporting the solar barque of Amun once a year from the sanctuary of Karnak to that of the Luxor Temple, using the dromos. This procession is symbolized today by the copy of the solar barque displayed on the dromos, opposite the temple.

The point in showing us this building in the evening quickly became apparent to us as dusk set in: in fact, at this time of the day, warm-colored lamps begin to light up every corner of the temple, its facade, and the androsphinxes that border the dromos, giving the whole place an eerie atmosphere that is, in my opinion, absolutely gorgeous. So, for the photos, there will be three chapters:

1 - The mosque

2 - Statues and columns

3 - Lights at dusk over the façade and the dromos

(Those three are from Cecilia Camus)

(Photos by Mireille Legros)

(Photos by Mireille Legros)

(Photos by Cecilia Camus)

... and yes, if some mocking minds like me were wondering, all the colossi that stand and sit in front of the first pylon, and the two that sit, in the "great courtyard of Ramesses II", on either side of the entrance to the "colonnade of Amenhotep III", all represent Ramesses II (😂!):

(7 photos by myself, then 1 by Cecilia Camus)

15th April

That day, we would spend the afternoon in transit towards Cairo (airport formalities, the flight (on a Boeing, therefore a whole dangerous and terrifying adventure in itself), waiting for the minibus to drive to the hotel, etc.).

But in the morning, we returned to the Theban necropolis.

First stop: Hatshepsut's mortuary temple.

Despite the significant damage it has suffered (see below), the temple is magnificent and its structure is extremely different from anything we had seen until then. Entirely in limestone, no pylons, vast terraces connected by a long stairway... Are those innovations on the part of the architect Senenmut, or, on the contrary, the customary freedom of a time set before a rigid fixation of Egypt's religious architectural conventions? I haven't seen enough temples to have an informed idea on the matter, but, in any case, the female pharaoh has an undoubtedly classy temple.

As we didn't have a helicopter or a drone, for once I will get help from a photographer from outside our group to give you a real overview of the temple, which seems essential to appreciate the beauty of this structure:

Photo by Wouter Hagens, 3th February 2010. See Wikimedia Commons.

The bas-reliefs (which depict, among other things, the settlement of the Egyptian people on the banks of the Nile) are both sufficiently well preserved for us to find here and there traces of intact painting, and very much damaged , partly by intentional acts of defacing the walls. This is not the first time that we have found, during this trip, temple walls vandalized in this way, and usually, the scumbags who scratched the reliefs to erase them are Orthodox Christians who seized the temples to turn them into churches or monasteries, during the era of Roman domination and after. In this case, though, it was the supporters of Thutmose III who attacked the temple of the “usurper” after her death. That's how the guide explained it to us, and the practice (of trying to erase the memory of a reprobate) is known throughout Ancient times, and in Ancient Egypt Hatshepsut was one of the most famous victims of it, along with Akhenaten and his family later on.

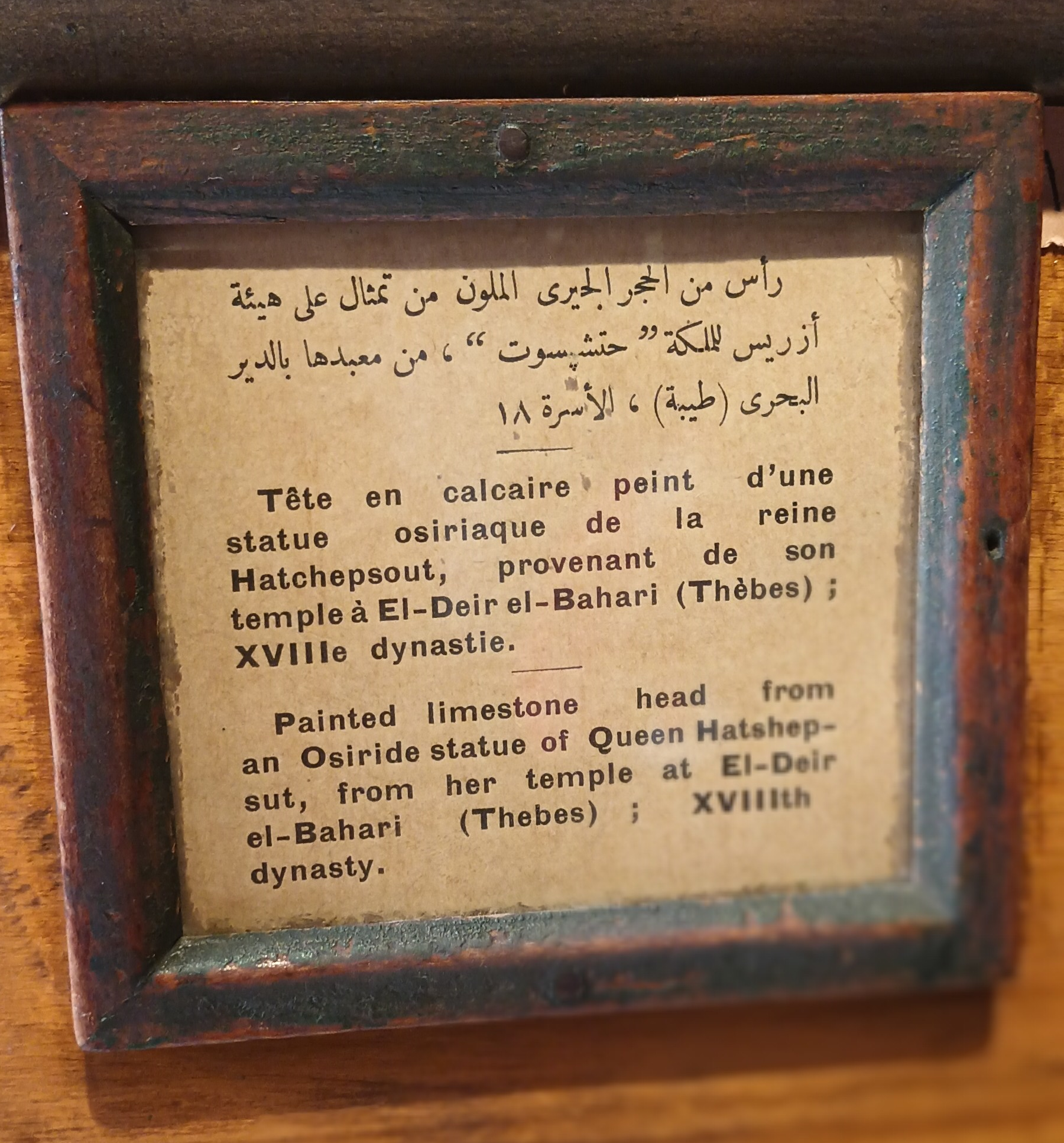

Hatshepsut has her share of Osiriac statues lining the terraces of the temple, though (wearing the pschent (the double crown symbolizing Upper and Lower Egypt combined) and a false beard on the chin (another pharaonic attribute)). Those statues are neither as omnipresent nor as huge as those favored by her distant successor Ramesses II, but this (relative) modesty is perhaps yet another way of being classy.

(This comes from my mobile phone. I don't know who, Cecilia Camus or Mireille Legros, took the shot.)

(Photo by Mireille Legros)

(Photo by Cecilia Camus)

The day before, we saw, with the colossi of Memnon, what a place looks like when there was a temple and there is almost nothing left of it. Next to the temple of Hatshepsut, we were now able to discover what a place looks like when there was a pyramid and only scattered ruins remain:

The entrance to the temple is guarded by two androsphinxes, including one with a face painted to be particularly expressive (according to the guide, as if they had tried to give the impression that it wears makeup):

(Photo de Cecilia Camus)

In conclusion to this beautiful visit, here are a few shots of us with the temple in the background:

(I don't know who took that shot. It was with my mobile again.)

Photos by Mireille Legros) -->

Once dazzled, by the sun as much as by the splendid architectural creation of Senenmut, we left Deir el-Bahari (the part of the necropolis that features the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut, that of her stepson and posthumous nemesis Thutmose III, and that of their very distant predecessor Mentuhotep I) to drive for a few minutes in a minibus to Deir el-Medina, the valley where sits the village and the tombs of the artisans who built the mortuary temples of the necropolis and dug and decorated the tombs of the Valleys of Kings, Queens and Nobles. (Those are the same workers I spoke about earlier, the ones who carried out the first strike in history, during the reign of Ramesses III (and, according to our guide, during the construction of the temple of Medinet Habu))

So, first, here is a map to recap those two days in Luxor and picture where everything is:

Now, the photos below show what remains of the artisans' village (They lived permanently in the necropolis, where all the sites where they worked were located - and they didn't have the right to cross the Nile to reach the city of Thebes (Amr described this ban as an ostracization of the inhabitants of the west bank, the place for the dead, by the frightened/disgusted/superstitious residents of the east bank, the place of the living — but a website on Deir el-Medina points out that it was also a matter of security: the royal tombs were the constant target of tomb robbers, and the artisans of Deir el-Medina happened to know where the tombs were, and thus, to be able to inform possible aspiring thieves from the east bank)).

(Photos de Mireille Legros)

(Photos de Cecilia Camus)

But what's most amazing in Deir el-Medina are the tombs of the artisans. Because between two periods of hard work digging and decorating those of the powerful, the workers also made their own tombs, somewhat on the same model as those of the pharaohs, but with much less means and time, which means that those tombs are much smaller, and it is more difficult, for modern explorers like us, to move around inside them...

(Photos by Mireille Legros)

... However, from an artistic point of view, the craftsmen of Deir el-Medina spared no effort to adorn the walls of their "eternal houses" with paintings that compare pretty well to their bosses' tombs'. I can even say that, after having been dazzled by the work and the splendid preservation found in the royal tombs, we were perhaps even more amazed in the tombs of the artisans, where the preservation of the paintings is even more perfect. As a result, in these small, modest vaults, we were enveloped in dazzling colours which do justice to the vivid mythological imagination of the ancient Egyptians, just as well as the larger tombs visited the day before.

So here are the pictures I took in the three tombs that we were able to visit, belonging to three of Ramesses II's workers, named Amennakht, Nebenmaat and Khaemteri (only the last photo, of the sign which identifies the tombs' owners, is by Mireille Legros):

And that was the end of our cruise in Upper Egypt. Goodbye Amr. Goodbye Nile Capital. Goodbye Aswan and Luxor, Nubia and Thebes (and by the way, I had finished Death on the Nile the night before, so I had the silly satisfaction of actually reading it entirely on the Nile). The rest (and the end) of our stay would take place in the megalopolis of Cairo (because yes, spoiler: no part of our Boeing fell during the flight, so we arrived safely in Cairo).

(Photo de Mireille Legros)

16th April

Day of the Pyramids!

One surprising thing about this trip is that, on the one hand, it was completely improvised by the agency that supervised us on site (they completely disrupted the programme established by the travel agency we had dealt with in France — the content remained the same, but the order of the visits was unrecognizable (the determining factor being the possibility of booking rooms on the boat), and, on the other hand, despite this chaos, the sequence of visits was characterized by great chronological coherence: as we sailed down the Nile, we went back in time, starting with visiting Ptolemaic and Greco-Roman temples (333-30 BCE), therefore constructions from the end of the pharaonic civilization (Edfu, Kom Ombo, Philæ), then we moved on to Abu Simbel and several tombs and temples of Luxor which all date from the New Kingdom (1550-1069 BCE). Besides, we ended the Luxor stay specifically with Hatshepsut who predates the various Ramsesseses we visited before. (The only exception that comes to mind is the temple of Medinet Habu (mortuary temple of Ramesses III) which we visited after having visited Abu Simbel (temple of Ramesses II), but distances being what they are, it was difficult to do otherwise.)

Finally, by ending the journey in Cairo, a sprawling city which extends around the site of Memphis (which was the capital before Thebes), we continue to travel further down the river of time, into the past. In particular, after having seen the dug and richly decorated tombs of the Valley of the Kings, we were now going to become better acquainted with the pyramids of Giza and Saqqara, burials that are much older than those of the Theban necropolis, since they date back to the Old Kingdom (2635-2150 BCE). In addition, our new guide, a sparkling Egyptologist named Kariman, first took us to Giza, to see the famous smooth pyramids of Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure (2589-2503 BCE), and then, we went to Saqqara to see the step pyramid of Djoser (2686-2667 BCE), the founding pharaoh of the Old Kingdom, who reigned well before the Giza Three. (This is much more methodical than the time travels of Marty McFly and Emmett Brown.)

First of all, you can probably imagine that, on the bus driving us to Giza early in the morning, we were already swooning at the ghostly views of the pyramids standing out behind the Cairo skyline, like the Pyrenees on the ring road to Toulouse on a clear day:

(Photos by Cecilia Camus, except for the last one, from Mireille Legros)

Then we arrived at the foot of the pyramid of Khufu, nicknamed "Great Pyramid of Giza" because it is the largest (and it is also the oldest, since Khufu was the father of Khafre and the grandfather of Menkaure), and we began to snap away at it:

Commentary:

1) As a child of the high tech age and in particular of the Paint software (see the maps displayed above), the optical phenomenon which makes the pyramids look smooth from afar while we see they are not when we come closer obviously made me think of the pixels in a digital image. (But of course, originally, they were really smooth, due to a thin layer of white limestone (reflective, too) which covered them; but, as Gaspar Noé has it, time destroys everything).

2) Kariman's explanation of the presence of a mortuary temple right next to the pyramid: unlike what happened in the Theban necropolis, where mortuary temples were built here and there while the royal tombs were grouped in the Valleys of the Kings and Queens, the megalomaniacs from the Old Kingdom who had pyramids erected also had an entire funerary complex built around their pyramid, including the mortuary temple and, usually, smaller pyramids, or less elaborate tombs, for their loved ones. For instance, Giza is not really just three pyramids and a huge sphinx. It's all of this:

I will have some things to add on that matter in a few lines, but first, it is time for a first "photoshoot" moment involving the stars of this trip:

(Photo by Mireille Legros)

(Photo by Cecilia Camus)

As the two photos above indicate, you can't have Khufu without Khafre. Indeed, whereas we had to briefly take the bus again to go to the grandson's pyramid (Menkaure), the son Khafre really had his pyramid (whose initial layer of limestone is still present at the top) right next to his father's (and, as the guide explained to us, Khafre had his built on a slightly higher plot of land, so that the son's pyramid can reach higher than the father's without being actually taller. This was a way of not offending the dad (a "cruel tyrant" according to Diodorus and Herodotus) by not surpassing his phallic symbol with a bigger phallic symbol, but still beating him at this childish game without seeming to. Freud must have been a fan of this story when it was told to him.

(The last photo in the gallery above was shot by Sylviane Camus)

My mother quietly sits with Khufu:

My sister prefers Khafre (photo by Mireille Legros):

She convinces my mother:

... who therefore decides it's better for her to enjoy the company of both pharaohs at the same time (photo by Cecilia Camus):

It was possible, by paying an additional fee, to enter the Pyramid of Khufu. Kariman, however, explained to us that we would not see much more than in the "subsidiary" pyramid the entrance to which was already planned in the programme. Indeed, if the teams of Deir el-Medina did, as we saw earlier, a fantastic job decorating the walls of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings, the builders of the pyramids had, for their part, a mission infinitely longer, more difficult, a true logistical hell, a task that took many years to perform, and which must have killed many workers from exhaustion. So suffice to say that once it was finished, they didn't care a bit about the decor. The tribute to the gods, to the celestial Nile, to the splendor of the afterlife, was already accomplished by the very fact of having erected those immense, impossible things. No need, as a bonus, to cover the walls with sublime bas-reliefs and multicolored paintings.

So we didn't enter the Great Pyramid (nor those of Khafre or Menkaure), but we did descend into a micro-pyramid adjoining Khufu's: that of Queen Hetepheres I, wife of Pharaoh Sneferu and mother of Khufu (see the map of Giza posted above).

(Photo by Cecilia Camus)

Let's hope that it was a little more carefully designed at the start and that it was again the ravages of time that put it in this state, because if in addition to being a "cruel tyrant" and a scary and petty father for Khafre, Khufu was also an ungrateful and unworthy son, then it's becoming a bit much for a single man, even a pharaoh.

I told you the day before that it was not easy to get around in the tombs of the artisans of Deir el-Medina. Yet that is nothing compared to this pyramid, the visit of which is literally a test of strength and balance. I re-emerged with the heart beating wildly (and the head painful from hitting it several times).

(A mixture of photos by Cecilia Camus and Mireille Legros, obviously)

And indeed, when you reach the end, you do feel like you are in a real vault, not in one of those genteel salons that the Theban pharaohs would later arrange to be their tombs:

(One photo by Cecilia Camus; another by an anonymous and helpful fellow explorer)

Of course, after that, we completed our visit to the Giza plateau with a reconnoissance (and photoshooting) tour around the pyramid of Menkaure, a.k.a. "Scarface" (this is, of course, not an official nickname, I'm the one who just decided to call that pyramid this way, because yes, it has a huge scar on its north face (made by the Mamluks in the Middle Ages, as they dug a good part of this enormous breach, trying to find out the entrance to the inside chambers of the pyramid - and that destruction was continued, with the same goal, by British and Italian Egyptologists Richard William Howard Vyse and Giovanni Battista Caviglia, in the 19th century; Caviglia even blew up part of the facade with gunpowder to dig a tunnel into it - now we can say that it gives a pleasantly odd appearance to this pyramid, and that it is nice that, between the uneroded limestone top of Khafre's and the scar on that one, history has given character to these buildings, even though they were originally made to all look alike; but the fact remains that all those "explorers" with their brutish methods were a bunch of assholes)):

(30 photos by myself, then 3 photos by Mireille Legros, then 1 by Cecilia Camus)

We weren't offered a visit inside that one at all. Which is a shame, apparently — because, unlike the pyramids of his predecessors, Menkaure's reportedly has a slightly more elaborate and interesting interior architecture, a sort of beginning of an attempt to rudimentarily sculpt a kind of palace decor. Let this missed opportunity not stop anyone from smiling from ear to ear when discovering this magnificent family photo with Scarface in the background:

(Photo by Mireille Legros)

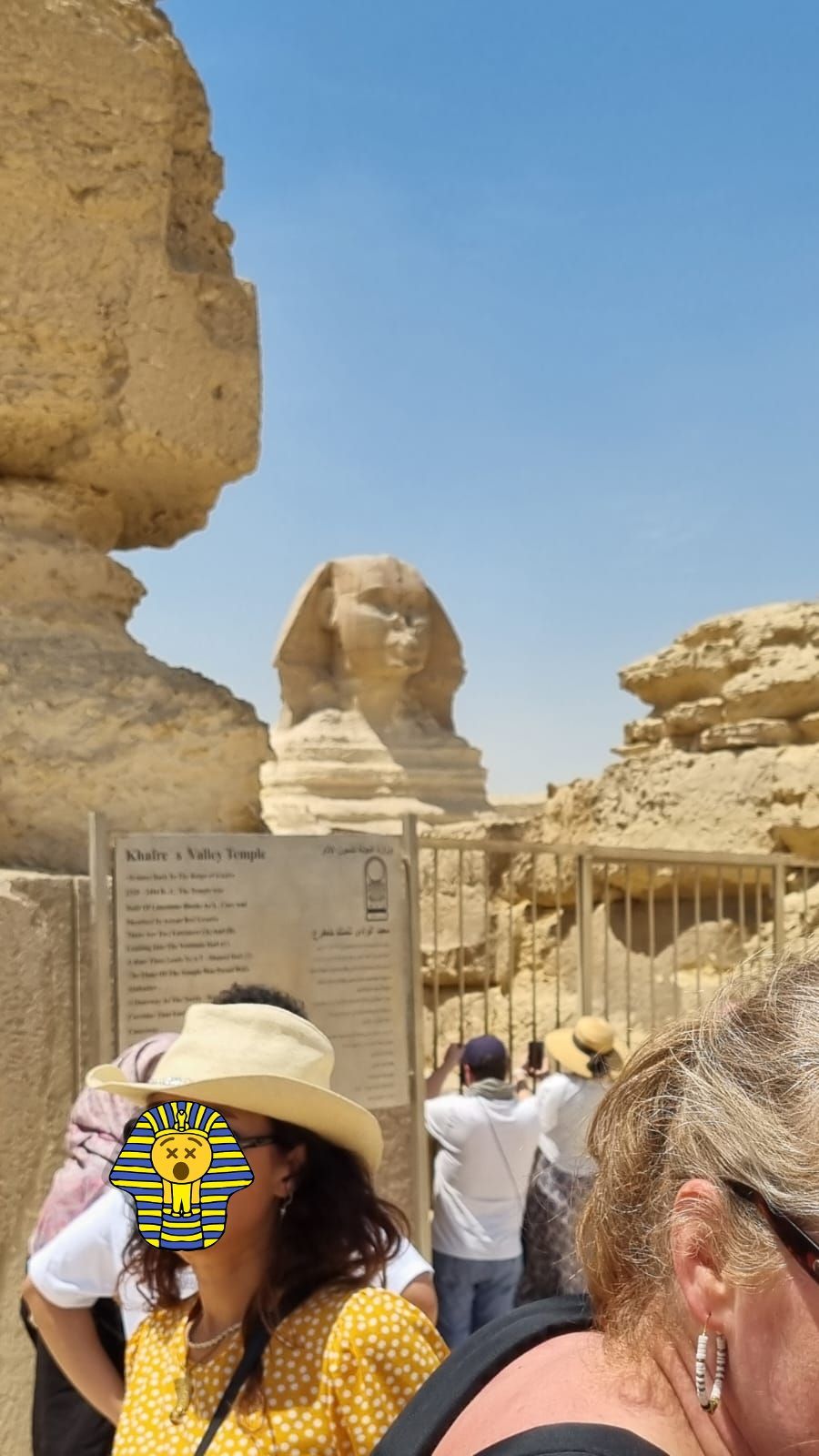

Obviously, we also paid a visit to the Great Sphinx of Giza, the famous and gigantic limestone androsphinx with the face of Khufu or Khafre, depending on the interpretations (but without a nose, thanks to the medieval iconoclastic Sufi Muhammad Sa'im al-Dahr (rather than Obelix, Napoleon or the Mamluks)), and which is supposed to have been, in any case, built on the orders of Khafre. Directly carved from a monolithic block weighing approximately 20,000 tons, the oldest known giant statue in Egypt, the largest monolithic statue in the world, also has two small temples in front of its front paws, the Sphinx Temple and Khafre's Valley Temple (through which we passed to climb a promontory from where we could take pics of ourselves in front of the beast).

(11 photos by myself et 13 photos by Mireille Legros, jumbled)

(If I remember well, these two pics come from Cecilia Camus's mobile phone, she took the picture of me and I took the picture of her)

Finally, before leaving Giza, we were allowed a strategically positioned bus stop so we could take panoramic photos of the three pyramids together, because of course, come on!:

... and I even managed to take one with the three pyramids together with a building that, just like the stele with the smiley face in Karnak (see above), could legitimately be posted in the funny Facebook group "Thing with Faces":

As it was half past twelve, and as breakfast dated back to 6am, one could have thought that the next stop would be the restaurant. No way! It was a one-and-a-half-hour tour of the site of what remains of Memphis.

So it was a small swerve in the harmonious chronological progression from the least ancient time to the oldest time that I described earlier. Indeed, if Memphis was the capital of the Old Kingdom, it remained important thereafter (when Thebes became capital in the Middle Kingdom) and it even regained the official status of capital in the second part of the New Kingdom, under the reign of Tutankhamun, after his father Akhenaten tried to found his own new religion and his own capital (Amarna/Akhetaten) - but we saw that Tutankhamun and the Ramessid pharaohs who came after him (those who were nearly all called Ramesses) were still very much Theban, especially in their necropolitan preferences.

As a result of this varying status, the small open-air museum that tourists walk through today when they go to "see Memphis" contains vestiges from several eras, a sort of little hodgepodge where we wandered around, relatively quickly, trying as best we could to catch the explanations of a guide who, as I said, is sparkling.

- a colossus bearing the image of Ramesses II (yeah, again... people don't lie when they tell you he was obsessed):

- the triad of the patron deities of Memphis (in Edfu, it was Horus, his wife Hathor and their son Harsomtus, in Thebes, it was Amun, his wife Mut and their son Khonshu; in Memphis, it is Ptah, his wife Sekhmet and their son Nefertem) (or maybe it's Ramesses II who got himself sculpted with Ptah and Sekhmet — there are some statues like that):

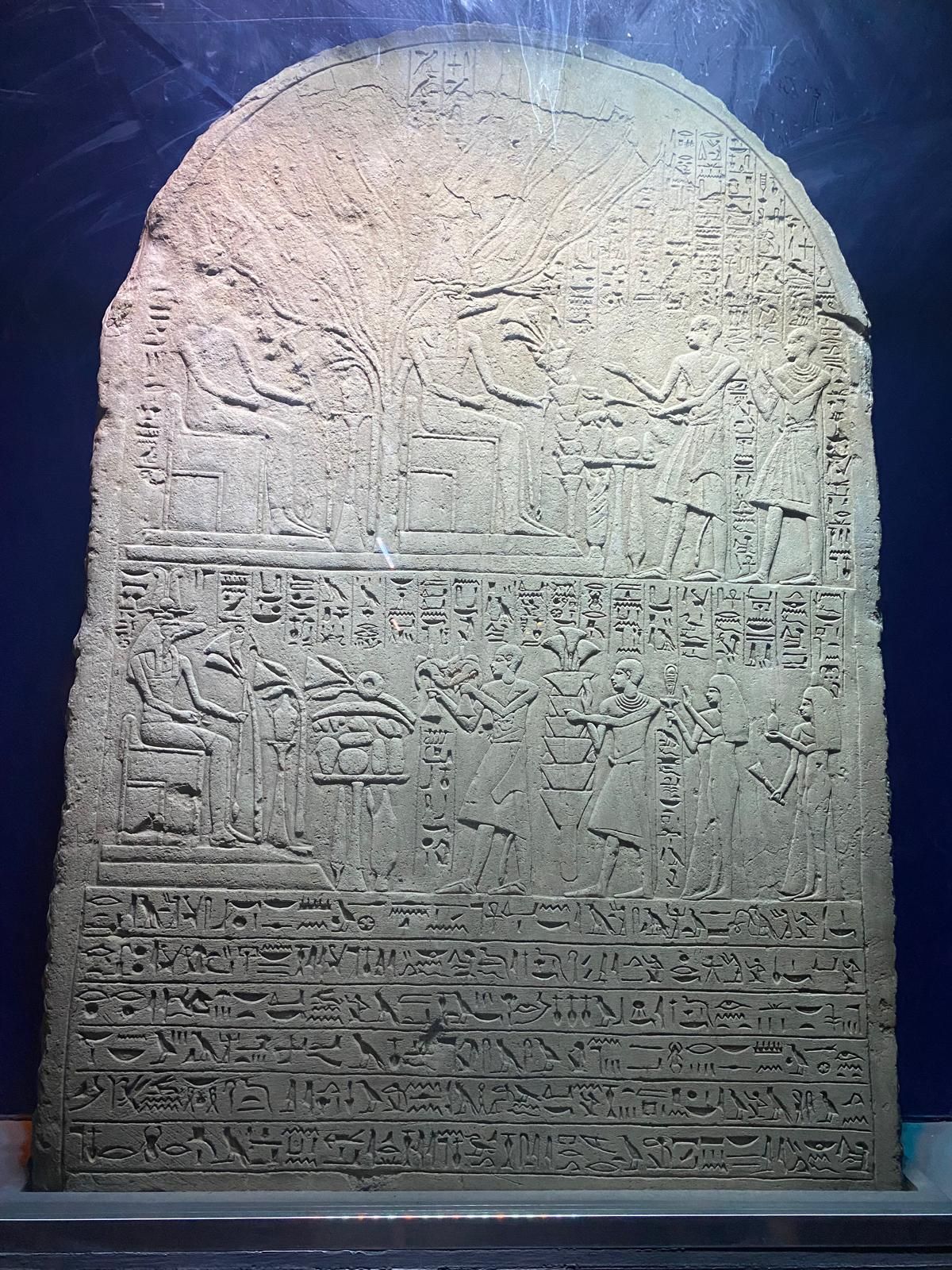

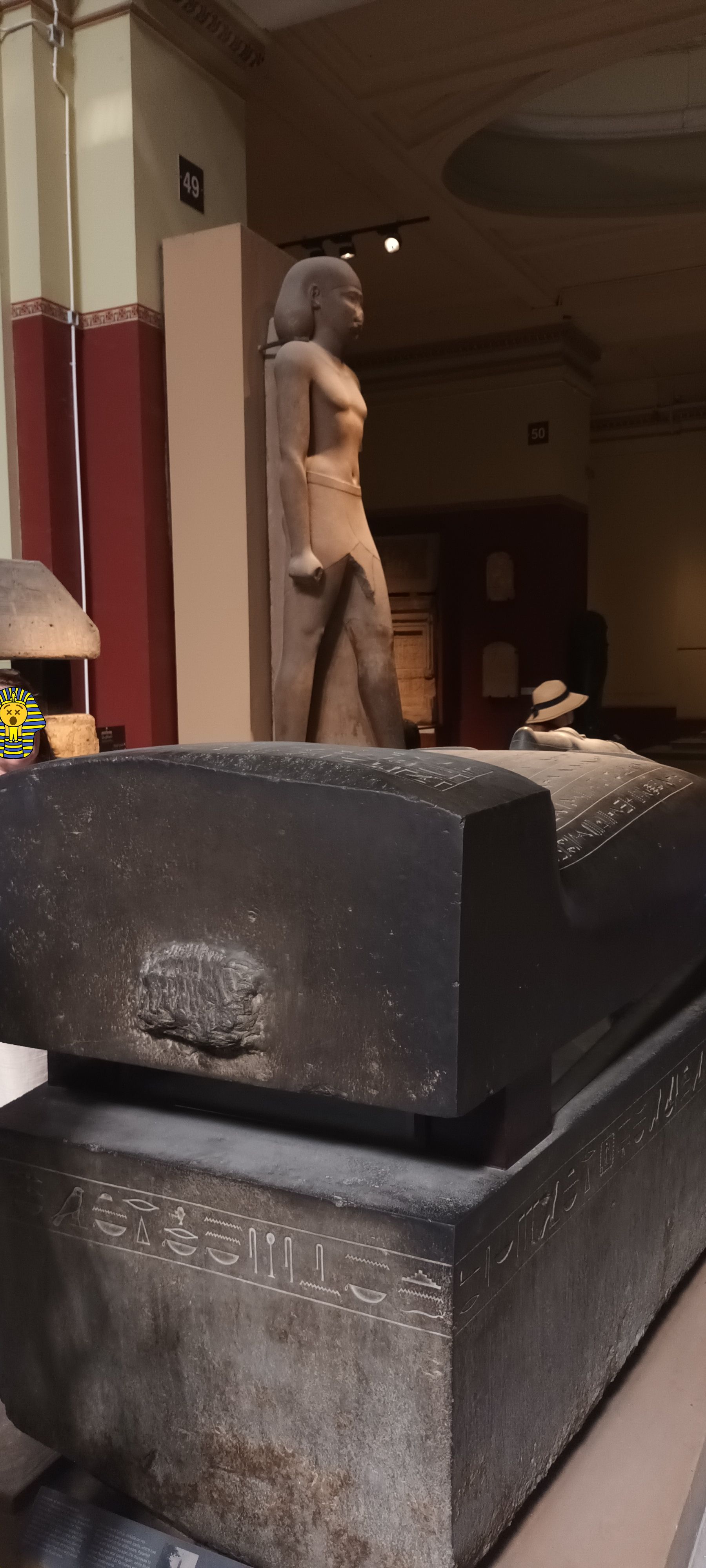

- a beautiful and massive engraved stone sarcophagus, of which I wasn't able to get the owner's name, if that information was ever given to us (some Internet users claim that he is one "Imen Hetep Hwi", but since Googling that name gives nothing, I won't be able to be much more definitive or helpful):

- various statues, steles, pieces de columns et debris:

- the remains of a statue of a little person (Kariman made a point to point out the model's dwarfism, and to explain that such people enjoyed reverence and a high social status in ancient Egypt):

- and yet another gigantic Ramesses II (no, I'm not joking):

After having (finally) had lunch

(at 2 p.m.),

...we got back on the bus and headed for the Saqqara plateau, the oldest part of the Memphis necropolis, which then extended to the plateau of Dahshur, then to that of Giza.

(Photo by Mireille Legros)

(Photo by Mireille Legros)

(Photo by Sylviane Camus)

According to Kariman, we could have spent a whole day just exploring Saqqara. But at that time (3:30 p.m.) we didn't have a full day (especially since almost all the sites close around 5 p.m. in Cairo), so we only visited the funerary complex of Djoser — which means that we walked briskly around the pyramid of Djoser (the first pharaoh of the Old Kingdom, and his pyramid (which was designed by Imhotep, the vizier of Djoser, a sort of super-genius, both architect and doctor, who would later be deified) is the first pyramid (before, the Egyptian monarchs were buried under funerary buildings of more reasonable size, mastabas, whose base was already a little wider than the roof, so they can be seen as rough drafts of pyramids, in terms of shape).

Yes, the first pyramid, and those that followed, were not smooth at all: they had a stepped shape — as if several smaller and smaller mastabas had been piled on top of each other, and, actually, that might have been the idea. It was Sneferu, later, who would try as best he could to build smooth pyramids, including a failed one at Dahshur, the so-called "Bent Pyramid", one that was cobbled together after the fact from a stepped structure at Meidum , and a successful one, finally, in Dahshur.

But for now, we're still in Djoser's time, the pyramid is a stepped one, and we're marching around it.

It's called a "funerary complex" because, of course, just as it is for the Giza Three, there's not just the pyramid: there are other buildings around it, built to complement the pyramid: temples, subsidiary tombs...

(14 photos by myself, then 4 photos by Mireille Legros)

... a "serdab", or "tomb of the ka" of Djoser (as a reminder, the ka, is the "ethereal double" of the deceased, which travels on a celestial barque to go get its heart weighed by Anubis, Osiris, etc.) (the serdab is a type of building that is specific to the Old Kingdom, a kind of small burial chamber that is closed and without windows, and contains a statue of the deceased, supposed to be his ka) (we were not able (because we're not that good at this sort of thing) to get a good photo of the statue, through the peephole pierced into the wall of Djoser's serdab, but it doesn't matter, as today the statue in there is a replica; the original statue de Djoser, the one that was found in the serdab originally, is at the Tahrir Square museum, which we were going to visit the day after...

(The first attempt to get a pic of the statue is mine, the second is Mireille Legros'. The other photos are mine.)

... a surrounding wall whose door takes visitors through a hypostyle corridor before they can reach the desert "courtyard" where the pyramid sits...

Finally, we were able to take photos of the two entrances to the pyramid (one, to the north, dug during the time of Djoser and leading directly to the underground burial chamber (which supports the idea that the pyramid was designed, originally, as a mastaba, and that its evolution towards a new, more monumental shape came later), and the other, to the south, dug towards the end of the history of Pharaonic Egypt, by the Saites, one of the dynasties of the Late Period. Neither of those entrances is open to the public, for security reasons (high risk of crumbling, restoration work in progress for a very long time) except that — as Kariman testifies, because she was invited, or hired as a guide, or both — once, when representatives of Christian Dior came to organize a fashion show in Cairo, the authorities let them in 🙄.

(3 photos of the north entrance by Mireille Legros, then 2 photos of the south entrance by myself, then 2 other photos of the south entrance by Mireille Legros)

17th April

So, now, on this last day spent visiting downtown Cairo before leaving Egyptian soil, my story of a methodical journey back in time, from the Ptolemy to Djoser and why not to King Scorpio, is completely blown apart. Because on this day, we're going to start in the middle of the Muslim Middle Ages, during the Crusades, with a detour through the 19th century (by visiting the Citadel of Saladin), then we will walk on a tightrope between Roman and Christian domination and Muslim conquest (by strolling through the Coptic district), and then we will end up in the "Egyptian Museum of Cairo", on Tahrir Square, which takes us back to the pharaohs, but which is much more wildly all over the place than the open-air Memphis museum is.

So, the bus started by dropping us off, early in the morning as usual, in front of the robust fortified wall of the Citadel of Cairo, a.k.a. the Citadel of Saladin, since it is Saladin, a Fatimid vizier of Egypt from 1168 to 1174, who then became the first Ayyubid Sultan of Egypt and Syria from 1174 to 1193, who had this vast fortress built (between 1173 and 1183) to protect the city of Cairo, since he was at war with the crusaders kind of all the time.

(6 photos by myself, then 2 by Cecilia Camus or Mireille Legros)

We then spent two or three hours, i think, wandering through the modern streets encircled by the medieval wall, from one visiting site to another, in a setting very reminiscent of our own fortified cities, sometimes with slightly different shapes which remind us that this ist the Arab-Muslim Middle Ages (or even, for the first photo below, a not-really-medieval North Africa), and the main attraction is the presence of several mosques from various periods inside the citadel.

Then again, there are many things to visit in the Citadel, and we actually saw only a small part of it:

GD-EG-Citadelle_du_Caire-map.png: Néfermaât (original version) GD-EG-Citadelle du Caire-map.svg: Malyszkz (version used for modifications) English-labelled version: modifications by Robert Prazeres, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

We passed by some of those buildings, without entering them...

... and I can't say that I resent skipping the police museum! (Ⓐ😛) ... although we did visit the former prison and part of the military museum, so I wasn't completely able to escape that kind of stuff... 😒

The first visit we made inside the citadel was to the Sulayman Pasha Mosque, the first Ottoman mosque in Egypt (The Ottoman Empire having taken control of the country in 1517, and Hadım Suleiman Pasha, the sponsor of the mosque, was governor of Egypt between 1525 and 1535, and between 1537 and 1538. As for the mosque itself, it dates from 1528, and it is definitely a nice building):

Then we came out in front of a large square, with, in the background, the former palace and harem of Muhammad Ali, which became a military museum in 1949. We didn't go in, but Kariman let us wander around the square and an open-air part of the museum which is to the side, and well, that's enough of a reminder - for the forgetful people who might not have noticed the omnipresence of uniforms almost everywhere throughout the stay — of the political atmosphere of the country.

To be fair, the whole thing starts relatively soft, on the square, very "heritage", with old cannons, and statues celebrating the two most famous presidents in the history of the current military regime (Nasser and Anwar el-Sadat), as well as an older (19th century) iconic war leader, Muhammad Ali's son, general and successor on the throne of Egypt, Ibrahim Pasha...

But, to the side, the mood is more Kim Jong Un than Tutankhamun:

(1 photo by myself, then 1 by Mireille Legros, then 4 by Cecilia Camus)

In addition, we then went to the prison (on the map above, it is located somewhere (although I don't know exactly where) on the side of the Mosque of Muhammad Ali and the building named Qa'a al-Ashrafiyya (which must be Al-Nasir Mohamed Ibn Qalawun's Ablaq palace, if I am to believe the French version of this map). It is an old military prison from the 19th century, opened under Isma'il Pasha, the son of Ibrahim and grandson of Muhammad, who reigned from 1863 to 1879, but the most recent parts were finished in 1882, and the prison did not actually close to become a museum until 1984.

(3 photos by myself, then 3 photos by Mireille Legros or Cecilia Camus, then 5 photos by myself

And, yet again, such good taste! (🙄):

(Photo by Mireille Legros or Cecilia Camus)

That was the end of the interlude dedicated to iron heels and the sound of marching feet, and then we were back to normal. More precisely, we climbed a few more steps towards another terrace, to find ourselves at a place that overlooks Cairo, offering us a breathtaking view of the extent of that sprawling city. Admittedly, while travelling by bus on their endless twelve-lane highways that end up as congested as a French dual carriageway at rush hour, we suspected that it is not strictly speaking a hamlet. But seen from above (for example from the ramparts of a citadel overlooking the city), you do get a clearer idea.

The two mosques that can be seen next to each other in the foreground (they are in fact only separated by a narrow pedestrian alley) are:

- on the left, the Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hasan, built between 1356 and 1363 on the order of the Mamluk sultan Al-Nasir Hasan (who reigned over Egypt from 1347 to 1351, then from 1354 to 1361, before being assassinated). It is also a madrasa (a school, in which students study Islam).

- on the right, the Al-Rifa'i mosque, built in the 19th century and containing the tombs of the monarchs of Muhammad Ali's dynasty, as well as that of the Shah of Iran (who took refuge in Egypt after the Iranian revolution).

As a matter of fact, since we are talking about mosques, the next (and last) part of the tour of the Citadel is precisely a mosque (indeed, there's plenty to see in that department, Cairo being nicknamed "the city of a thousand minarets" (but as the guide has it, the nickname dates from way back, and today it's more like ten thousand)).

More precisely, we ended the tour in the "Alabaster Mosque", or "Muhammad Ali mosque", built during the period between 1830 and 1848, by the order of the eponymous and oft-aforementioned monarch, founder of the last royal dynasty of Egypt (the Alawites (1805-1953)), and which seems (the mosque) to be by far the most famous "attraction" of the Citadel of Saladin. Admittedly, it is quite wow.

(A mixture of 6 photos by Cecilia Camus or Mireille Legros, and 10 photos by myself)

As it happens, the pretty ornate clock tower depicted below (and of which Kariman specified that the clock has never worked (although according to headlines it has finally been working since the restoration of the tower in 2021😉) was offered in 1845 to Muhammad Ali by Louis-Philippe, a gift made to Egypt in return for the Luxor obelisk offered by the same Muhammad Ali to Charles X in 1830 (see above):

(Photo by Cecilia Camus or Mireille Legros)

And at the same time, Louis-Philippe also offered the chandelier which sits in the center of the magical decor conjured up, inside the mosque, by shadows and lights, majestic domes and stained glass windows:

(1 photo by myself, then 10 photos by Cecilia Camus or Mireille Legros, then 5 photos by me again)

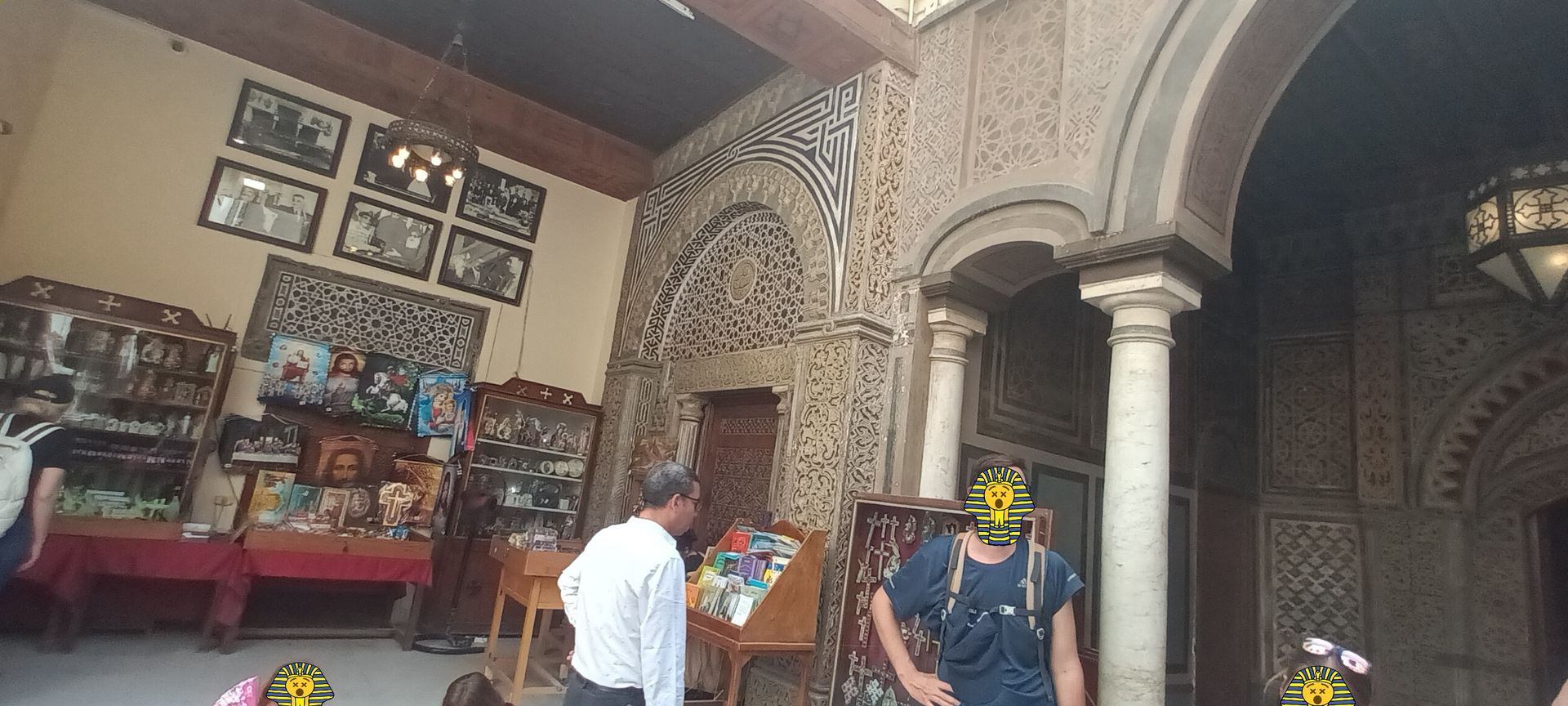

As our tour of the Citadel was over, the bus picked us up and took us to what tourist agencies call the "Coptic neighbourhood", what specialized websites seem to mainly call "Coptic Cairo", and what our guide prefers to call "the religious complex".

(The guide's arguments are that: 1°) there are not only churches, in this neighborhood, but also a synagogue, and the oldest mosque in Egypt; and 2°) “Coptic” did not designate, at the beginning, Egypt's Christians, as it does today; it was just the term used by the Arabs, when they conquered Egypt, to designate the natives, more or less direct descendants of the ancient Egyptians (thus, a comparison with their language, Coptic, enabled Champollion to decipher hieroglyphs) — and they were predominantly Christian at the time of the Arab conquest, but the term did not refer to their religion.) (But hey, since then, the "Coptic Church" was created; it is one of the

Oriental Orthodox churches, with its pope (Tawadros II) in Alexandria; in general Egypt's Christians belong to that church, and the term "Coptic" is now commonly used only to speak of them).

(1 photo by myself, then 2 photos by Mireille Legros, then 1 by Cecilia Camus)

The Coptic neighborhood is the oldest part of Cairo, already a Persian settlement in the 6th century BCE, later the site of a Roman fortress (the name "Babylon" was apparently given to the

Persian settlement and then to the

Roman fortress).

(7 photos by myself, then 1 by Cecilia Camus, then 2 by Mireille Legros)

The community was near the city of Heliopolis during the reigns of the Ptolemies, as well as Fustat, the first Arab capital of Egypt, founded in 641 CE (the Coptic neighborhood is now itself part of Fustat, and Fustat and Heliopolis have become districts of Cairo). When Egypt was massively converted to Christianity (albeit clandestinely at first), during the Roman era, by the evangelist Mark, who was based in Alexandria, the area of "Babylon" saw many churches built.

There are still many to visit, dating from various eras, and it is mainly those very old Orthodox churches that are meant when someone says they visit the Coptic neighbourhood.

In any case,

we saw, not necessarily in that order:

- Saint Virgin Mary's Church, nicknamed "the Hanging Church", because it is built high above the Roman walls of the fortress of Babylon. It dates from the 7th century CE, but was built on the site of an earlier church, which dated from the 4th century:

(5 photos by myself, then 1 by Cecilia Camus, then 4 by me, then 1 by Cecilia Camus, then 2 by me, then 1 by Cecilia Camus, then 2 by me, then 1 by Mireille Legros, then 52 by me, then 2 by Cecilia Camus, then 2 by Mireille Legros)

- Saints Sergius and Bacchus Church ("Abu Serga") a.k.a. "The Cavern Church", also dates from the 4th century, and was supposedly built in a place where Joseph, Mary and baby Jesus took refuge as they escaped the massacre of newborns ordered, in Judea, by Herod I (according to the episode from the Gospel according to Matthew entitled "Massacre of the innocents" and "flight into Egypt"). The "cavern" that gives the church its nickname is the underground crypt believed to be the cave where the "Holy Family" is said to have stayed, and Sergius and Bacchus, the eponymous saints/martyrs, were Roman officers, secretly Christian, who were tortured and killed in 300, in Syria, for refusing to take part in a sacrifice honoring the Roman gods.

(12 photos by myself, then 1 by Mireille Legros, by 19 by me, then 1 by Mireille Legros)

- The Church of St. George, or "Mar Girjis", is a large church built on a height (overlooking the Monastery of St. George, of which it is part), originally at the top of a round Romanesque tower. This is why it is circular in shape (and it is the only church of this shape in Egypt). It dates from the 10th century, but was rebuilt in the 19th century, and also, after a fire, between 1904 and 1909. It is dedicated to George of Lydda, a very popular martyr in the Middle East, executed in 303 following Diocletian's decree prohibiting the practice of Christianity. And the interior decoration of this church is kind of unique, compared to the other churches in the Coptic neighbourhood, and it is quite magnificent.

(1 photo by Cecilia Camus, 4 by myself, 1 by Mireille Legros, 13 by moi, 1 by Cecilia Camus, 1 by Mireille Legros, 6 by moi, 1 by Cecilia Camus, 1 by Mireille Legros, 1 by Cecilia Camus, 11 by me)

We also went to the Saint Barbara Church, named after Barbara of Heliopolis, another martyr from the time of Diocletian and Maximian (the church, for its part, dates from the 5th or 6th century (and was also rebuilt several times, including in the 11th century))...

(3 photos by Mireille Legros, then 1 by Cecilia Camus)

...and that's not all, since we passed through a nice narrow open-air but covered corridor, where the walls served as a second-hand bookseller's stall, but we got through too quickly for me to buy some of the interesting or amusing things that were there (including a treatise on Ancient Egyptian Black Magic (with a yellow cover that wasn't all that numinous😁) in the middle of picture books on Egyptian or Middle Eastern stars, or books on local history and geopolitics), and above all we also briefly visited the aforementioned synagogue (the Ben Ezra synagogue, essentially built in 1892, on the site of a previous synagogue (supposed to "go back" to Moses😁) of which parts remain), but we were forbidden to take photos... 👎

... then we had lunch (rather late once again).

And then we moved on to what would be the final visit of this trip: the Egyptian Museum, located in Tahrir Square, inaugurated in 1902, and containing one hundred rooms spread over two floors, and overflowing with 160,000 objects, all with a guide whose boundless energy I have already mentioned, and who had once again decided to show us everything in too little time, even if it meant that the explanations would be rushed. But this time, there was an additional disruptive element: we were equipped with audio headsets provided by the museum, and connected to a microphone worn by Kariman, which made it possible (in theory) not to miss a beat of her expert commentary, despite the mad rush through the museum. It was only theoretical, though, because these devices turned out to be extremely dysfunctional, and rather than not missing a beat, we ended up struggling to hear even the smallest snippet of her explanations.

(2 photos by Cecilia Camus, then 1 by myself, then 3 by Cecilia Camus)

So here are snippets (of the visit):

So, first, the entrance, which, as can already be seen above, is decorated with a large fountain in the center of which sit two red granite androsphinxes (discovered at Karnak, and bearing the face of Thutmose III), while between them stands an obelisk that bears the cartouche of Ramesses II and was discovered in the ruins of the city of Tanis (which is located in the Nile delta and was the Egyptian capital during the Third Intermediate Period, between the New Kingdom and the Late Period):

(Photo by Cecilia Camus or Mireille Legros)

...and that's not all: when we approach the main entrance, we pass by a (guess what) colossus depicting Ramesses II (😂), this time in a new role as standard bearer (there's nothing that guy couldn't do!):

Then, as can already be seen in two of the photos above, the atrium through which one enters the building contains a lot of sarcophagi, too many to really identify most of the owners (especially since we had a turbo guide and couldn't hear anything she said for the aforementioned reasons):

She still took the time to point out to us the granite sarcophagus of a little person, and to remind us, as she had done in Memphis, of the high, privileged, revered social status that this group enjoyed in ancient Egypt (but it is online sources that gave me the additional information that the owner was called Djeho and was buried in Saqqara, in the tomb of a man described as his "master" or his "patron"):

Another interesting artifact is the Narmer Palette, a siltstone cosmetic palette, dating from the end of the fourth millennium BCE (so, the 1st dynasty, before the Old Kingdom, in the so-called "Thinite Period") and the oldest evocation of the unification of the two Egypts by the founder of the 1st dynasty (Narmer), who thus became the first pharaoh:

(Photo by Cecilia Camus or Mireille Legros)

The museum also contains the statue of the ka of pharaoh Djoser (the real one, this time, not the replica that replaced it in the serdab, next to Djoser's Pyramid, and which, the day before in Saqqara, we didn't manage to see (nor to photograph) through the peephole pierced into the serdab):

Two granite colossi from Ptolemaic time face each other: one represents an official named Horemheb, who ruled over Naucratis, a Greek port settlement, and the other represents a king (albeit apparently unidentified (at least the museum's website doesn't give his name)):

Obviously, there is also a colossus depicting Ramesses II:

Surprisingly, though, when you stumble upon Khufu (even though he's the guy who did the Great Pyramid of Giza), it's in the shape of a Lilliputian statuette (made of ivory, and discovered in Abydos, in a temple dedicated to Osiris):

(Photo by Cecilia Camus or Mireille Legros)

... whereas his son, Khafre, the one with the less tall but higher pyramid, is this time much more overt in his active rivalry over size with his daddy (his statue is in diorite and was found in his valley temple, in Giza):

A colossus found in Karnak, depicting Senusret III, a pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom (therefore between the Old and New Kingdoms):

Also, perhaps until the receivers of stolen goods from the British Museum finally deign to return the real one to Egypt, the Tahrir Square museum is exhibiting a replica of the Rosetta Stone:

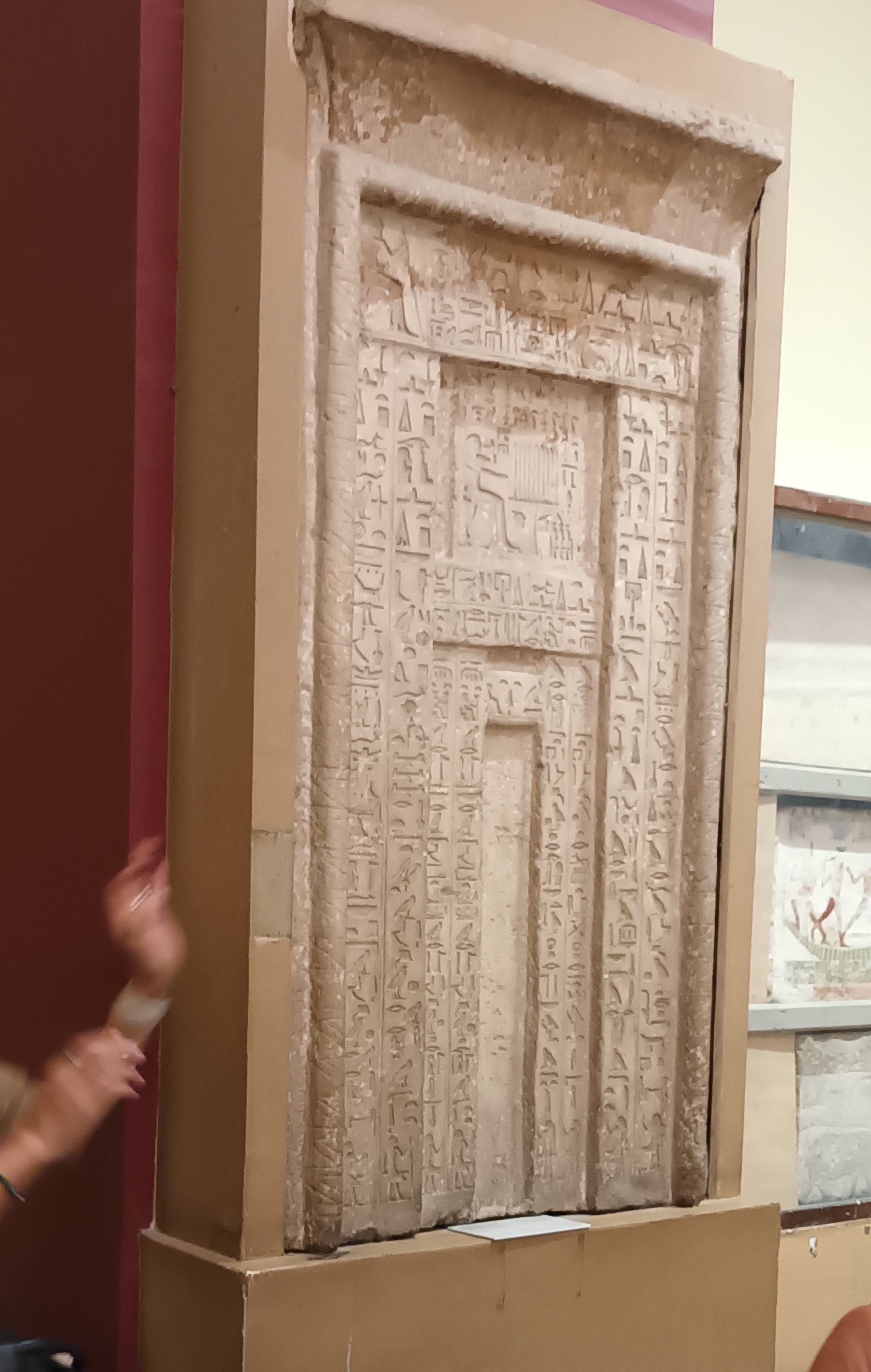

A false door of painted limestone, which was part of the layout of a mastaba at Saqqara, serving as a burial place for Tepemankh II, who was priest for Khufu and Menkaure, and purifying priest for the pyramids of Sneferu, Khafre, Menkaure, Userkaf and Sahure (such false doors were intended to serve as a “real” door to the “ba” of the deceased (an immaterial post-mortem manifestation, akin to the “soul”, distinct from the ka)):

False doors were actually a fairly common architectural element in mastabas. So there are a significant number of them in the museum. Here's another one that I photographed, although I have no idea where it comes from:

A strange custom of these belligerent nutjobs that were the pharaohs consisted in having small heads sculpted representing prisoners of war, to display them through the windows of their royal quarters, or to place them so as to often be stepped on, to symbolically tread on the faces of vanquished enemies. According to the museum's explanatory sign, the two diorite heads shown below were found at Saqqara, in the hypostyle corridor through which one enters the funerary complex of Djoser, and they were probably part of a threshold (for the aforementioned purpose). There are no details on the provenance or function of the two rows of heads lined behind them:

The triads of Menkaure are three statuary groups found in the valley temple of the funerary complex of Menkaure (so, built near his pyramid at Giza). All three represent:

- Menkaure at the centre, wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt

- goddess Hathor on the left

- the personification of one of the provinces of ancient Egypt (called "nomes"), a different one for each triad

The idea is, according to the museum's sign, to express the wishes of Menkaure (fertility and resurrection from Hathor, various offerings from the nomes)

Userkaf is the father and predecessor of pharaoh Sahure, and son and successor (with maybe another guy named Thampthis in between, but that's not sure) of Shepseskaf, who is himself the successor (and maybe the son, but that's not sure) of Menkaure. It was during the reign of Userkaf that the cult of Ra grew to the point that he became the main god of the religion of ancient Egypt. This pharaoh had a sun-temple built in Abusir, near Saqqara, the first of its kind (Egyptian sun-temples were both royal funerary complexes and religious buildings dedicated to royal worship, and, I imagine, the unintentional inspiration for the stupid name of an infamous modern cult (the Order of the Solar Temple)). Here's Userkaf's mug, in greywacke, wearing the red crown of Lower Egypt (found in 1957, in his sun-temple):

Many statues of scribes (because it was prestigious), or even, in the Old Kingdom, statues commissioned by lords, nomarchs or other important figures (to decorate their tombs), and they required to be depicted as scribes — the idea being that reading and writing were skills reserved for the elite, and which therefore looked particularly good on a résumé, for a deceased person who would like to maintain a high social status in the afterlife. Yep, post-mortem career plans. Talk about cosmic masochism...

- at the top, an unidentified scribe in painted limestone, in the middle of two of his colleagues, including, on the right, a statue in gray granite (found in Saqqara) of a man named Nimaatsed

- bottom centre and bottom right,

statue in sycamore wood (with copper and rock crystal eyes) of a scribe and priest

of the time of Userkaf, named Kaaper (the statue was discovered in his mastaba, in Saqqara)

(Photo by Cecilia Camus or Mireille Legros)

(Photo by Mireille Legros or Cecilia Camus)

Other Old Kingdom statues made with materials similar to some of the aforementioned scribes (painted limestone, with rock crystal, calcite and copper eyes): Prince Rahotep (son of Sneferu and brother of Khufu) and his wife Nofret (found in the mastaba of Rahotep, in Meidum):

More statues of little people, including someone named Perniankhu (top left, in painted basalt, discovered in his tomb at Giza), then the priest Knumhotep, top center, then, in the second photograph, the priest Seneb surrounded by his family (he was the funeral priest of Khufu and his son Djedefra, the statues are in painted limestone, and they were found in the mastaba of Seneb, in Giza). I have no idea who are the individuals standing to the right of Perniankhu and Knumhotep.

Both Seneb and Knumhotep were responsible for the wardrobe of the pharaohs they served, in addition to being priests (but at different times: Seneb was in office

at the end of the 5th dynasty and the beginning of the 6th, Knumhotep

later during the 6th (Perniankhu, for his part, is

a character from the 4th) So they still have in common that they are people of the Old Kingdom.

A small group pic, but of pharaohs whom I was essentially unable to identify (no time or sense to photograph their little explanatory signs; no help at all from the Internet) (maybe the taller one on the bottom right is Khafre?). In the middle, at any rate, there is Teti, a pharaoh of the 6th dynasty (so still the Old Kingdom), successor of Unas and predecessor of Userkare (the statue, in dark pink granite, was found in a well close to the funerary temple of Teti, near his pyramid, at Saqqara):

Same thing to the right of this paragraph: many statues exhibited together, only one of which I was able to identify thanks to the help of the web and web users — namely the character seated exactly in the middle, at the top. This is Ptahshepses, the son-in-law and vizier of the pharaoh Nyuserre Ini (of the 5th dynasty), who managed to monopolize many important functions: chief justice, directing an administration which controlled the country. The museum's sign also states that he was "prophet of Hathor and Ra". In short, quite a double or triple jobber - one wonders if Ramesses II was not a little inspired by him, much later, for his ambitions of temporal and cosmic omnipotence.

Below, a series of other groups of statues whose members I was unable to identify, for the same reasons as above, except for the wooden statue representing a female figure which is completely to the right in the last photo from the gallery: this is the wife of Kaaper, the aforementioned scribe and priest; it was discovered in her husband's mastaba, in Saqqara, at the same time as his statue.

Senusret III (a statue of granite found in Deir el-Bahari)...

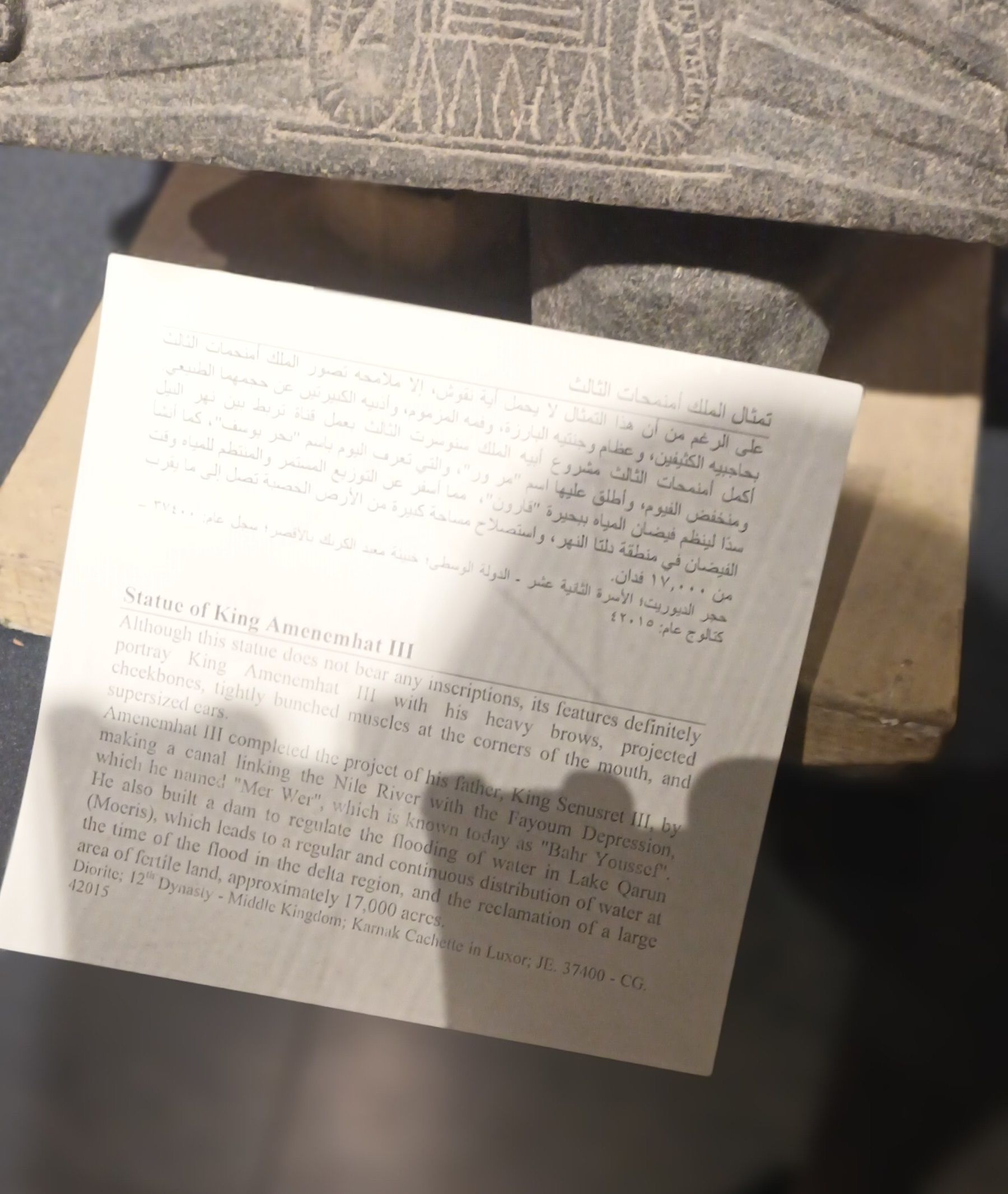

... and his son Amenhemat III (a diorite statue found in Karnak), who reigned with his father as co-regent for 20 years, and reigned 45 or 46years overall...

...and he seems to have been an ace at irrigation and regulating the use of water:

This diorite bust found in Fayum also shows Amenhemat III, this time dressed as a priest:

(Photo by Mireille Legros or Cecilia Camus)